Arabic Calligraphy & The Visual Arts

Arabic Calligraphy & The Visual Arts

By HASSAN MASSOUDY

The best way to address Arabic calligraphy in the field of contemporary art would, perhaps, be to consider it through the lens of my own personal experience, because I consider myself to be a visual artist and not a critic. As the Japanese saying goes: ‘Calligraphy is the man himself’, meaning that each calligrapher has a unique experience reflecting his own particular artistic path.

Hassan discusses his creative process at Sundaram Tagore Gallery, NY

Since my childhood, I have always been surrounded by Arabic calligraphy decorating the walls of architectural monuments, mosques, graveyards, religious schools and libraries in the city of Najaf in Iraq. I also discovered calligraphy through my uncle who was an orator, a writer and an amateur calligrapher as I watched him drawing calligraphic scripts with his qalam and black ink ever since I was five years old. At the age of ten, my calligraphies attracted the attention of my primary school teacher. Inspired by his warm encouragement, I participated in calligraphy exhibitions throughout the course of my continuing education, from primary to middle school.

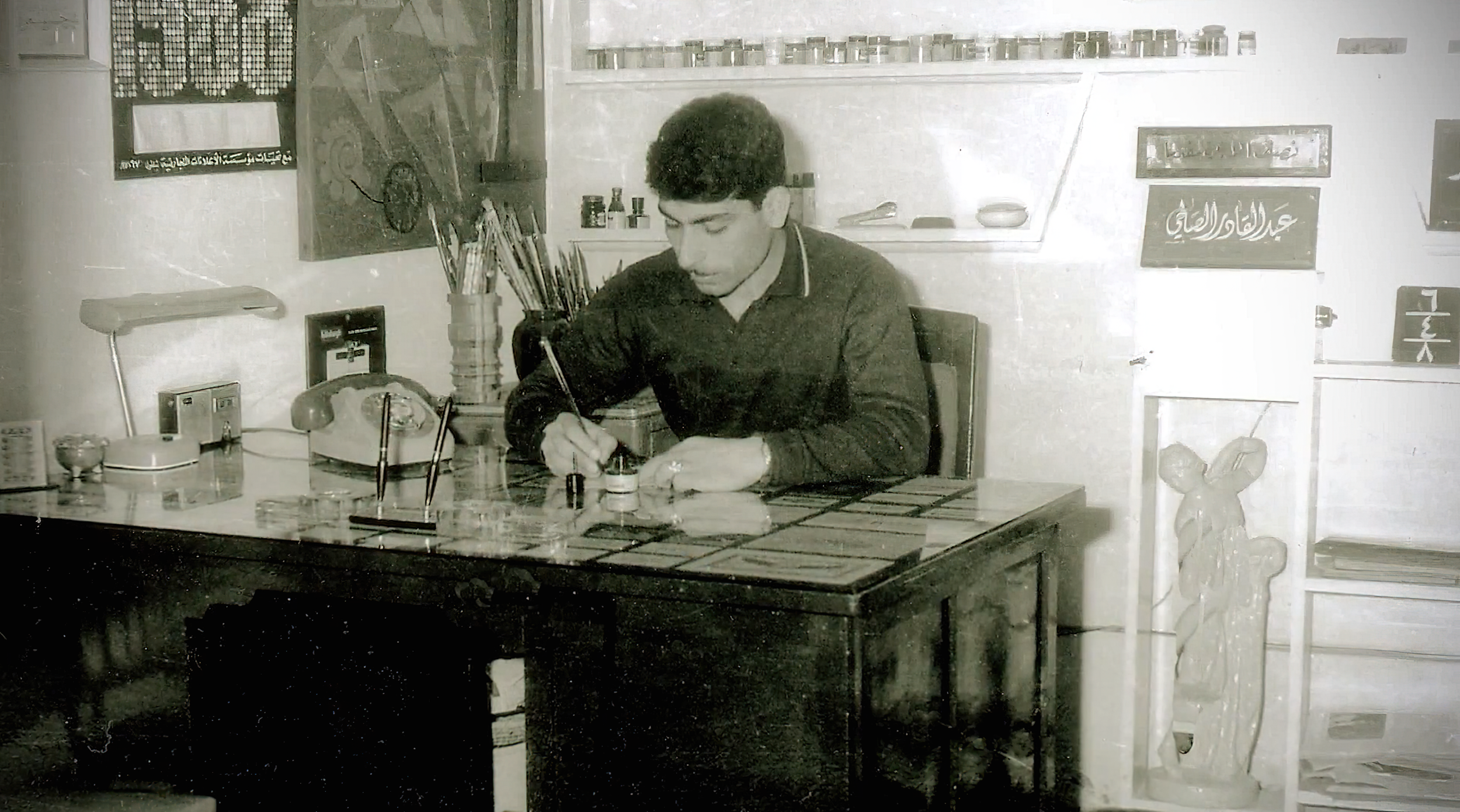

Moreover, whilst still relatively young, I designed a series of advertising posters for various shops in Najaf. In 1961, at the end of middle school, I moved to Baghdad and began to work with other calligraphers who taught me some aspects of calligraphic style and technique. At the same time, I also pursued a more commercial path of development related to advertising, whilst all the time being moved by a deep desire to express myself somehow through art, and constantly dreaming about studying in Paris.

After working as a calligrapher in Baghdad for eight years, I had the opportunity to travel to Paris, in 1969, where I entered the School of Fine Arts (L’Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts). I needed to learn everything about western art, from its Greek origins to the European Renaissance in the 16th century, and on until the 20th century, where various modern artistic movements were introduced. I also studied the basic techniques of the visual arts, such as oil painting and colour mixing processes, as well as parallel studies in visual perspective, architecture, mosaic, frescos and various theoretical courses. I had taken with me some qalams for calligraphy from Iraq and was able to contribute my calligraphic skills to an Algerian newspaper issued in Paris, which helped me to pay my tuition fees.

My academic journey at the Beaux-Arts lasted for five years, before I received the National Superior Diploma in Visual Arts, in 1975. At that time, artistically speaking, I felt as though I was heading towards a dead end and realized that I needed to discover my own personal style. At first, I developed an interest in artists whose paintings could be characterized as minimalist with expressive strokes, and this led me further towards abstract art, as I sought to capture its essential qualities. It is at this moment in time that Arabic calligraphy entered into my paintings. I was pleased by this reconciliation even though it was still mostly ornamental as I continued to work using oil on canvas. This situation didn’t satisfy my deeper artistic sense and gave me an appreciation of the importance of the material medium used in achieving certain kinds of artwork.

Following my eight years of experience working as a calligrapher in Baghdad and my five years of studying the visual arts in Paris, I still felt, in 1975, that I was neither a complete calligrapher, in the traditional sense of the term, nor a visual artist with sufficiently wide-ranging skills at the level of the diploma I had been granted. In fact, the calligraphy I learned in Baghdad no longer satisfied me, nor did the oil painting style I had been taught at the Beaux-Arts. So I started asking myself: ‘What are my options? Where should I go?’ And then an African proverb came to my mind: ‘When you don’t know where to go, remember where you come from.’ So I resumed learning Arabic calligraphy all over again.

What is Arabic calligraphy? Where does it come from? How did it evolve in the last thousand years?

I spent six years analysing all the documents I came across in libraries, museums or on the walls of monuments. Later still, I sought out the greatest living calligraphers, namely Hamed Al-Amadi in Istanbul and a group of calligraphers in Cairo, questioning them closely about matters I knew that I still didn’t fully comprehend.

The historical culture and the visual arts knowledge I had acquired at the Beaux-Arts allowed me to appreciate classical Arabic calligraphy from an entirely new perspective, considering the finest particularities of this art. I was able to summarize these six years of intensive research in a book entitled Living Arabic Calligraphy – first published in Paris in 1981, by Flammarion, which traces the technical, visual and social aspects of calligraphy, in both Arabic and French, using selected sequences of images and inscriptions.

Around this time, at the beginning of the 1980s, I left oil and canvas in favour of ink and paper, driven by a mysterious and deep-rooted desire. I now feel that paper and ink have mostly been used in the oriental arts, whereas oil and canvas were, for centuries, the distinctive media of western art. Furthermore, coloured material plays a psychological role: water-colours differ from colours obtained using oil, and paper that absorbs some of the ink differs from canvas covered with resin which prevents the absorption of colours.

At that same time, I also decided to work on abstract compositions based on the shapes of Arabic letters. But after a while, I became disillusioned with this path, as I was continuously producing similar forms and dealing with the same questions and solutions from a visual point of view. Words, however, have the capacity to impose shapes I hadn’t considered, through their meaning. Fire, for instance, naturally moves upwards, automatically suggesting a composition in the vertical plane, while water embraces the horizontal plane with its tendency to flow downwards.

‘I WISH TO BE A BUTTERFLY FLUTTERING AROUND THE CANDLE OF YOUR BEAUTY.’

—MACHRAB

The necessity of drawing calligraphic scripts based on texts, arose from this idea. But what statements should I then select? Knowing that this content should necessarily be broken down and rebuilt, I thought to choose literary texts that were at least capable of enduring this process. This is how Arabic poetry became more appropriate in the course of my artistic practice. On the one hand, poets would enrich me with their images, insights and feelings; and at the same time, poetry provides for a freedom of visual expression, illustrated by its ability to deconstruct words as well as the possibility of restructuring them. Poets also manipulate words in their own creative manner.

Addressing poetry has led me to contemplate the wide vistas of Arabic poetry since the infinite desert spaces at the time of Jahiliyah. When Arabs used to express themselves through poetry, calligraphy was still in its infancy. But the implicit creativeness of poetry held in its core the future development of Arabic calligraphy, for they both serve to magnify the shape and veil the meaning.

The ancient Arab poets who lived in the desert wrote poems that illustrated the immensity of the desert. Time and space were likewise asymptotic to infinity in the desert environment, and each person therefore felt as though they existed at the heart of a vast circle bounded only by the horizon. The distance to that horizon seemed equal on all sides and one could stand in the centre of this wide hemispherical space, illuminated by the light of day and by the stars at night. Pre-Islamic poetry was mainly about chants. Poets would create it like jewellery or in the manner of a skillful calligraphic composition, reflecting the desert space with a sober style and simple words.

‘YOU FLED TO THE DESERT ON THE WINGS OF THE HEART. THE DESERT IS LOST IN THE REALM OF YOUR HEART’

—RUMI

There is a major aspect of poetry that is also present in calligraphy. A poet doesn’t disclose all the words and meanings, inviting the listener to become involved in the poetic images and perhaps even to interpret them differently. This helps the reader, listener or viewer to include his own desires and express his more intimate feelings; thus the words of the poet merge with the listener’s unique insights garnered from personal experience.

Similarly, words also provide an opportunity for the reader to create his own imagery. This is of paramount importance for humans. In fact, the human brain needs to liberate its images and ideas every day, and poetry, like other artistic endeavours, allows for the expression of feelings. One can imagine oneself as a poet, whenever reading or listening to poetry. Calligraphy enjoys the same expressive abilities as poetry, and all arts can be interrelated in this fashion, each one paving the way for the other. The intersections between poetry and calligraphy thereby serve to enhance the visually expressive capabilities of the latter art.

I approach the work of a poet with the hope that their metaphors will enrich my visual artwork. This is why I am always seeking different environments, and like any artist, I am on the lookout for new inspiration, always hoping that my images will join with those of the poets, opening the way to new approaches. It pleases me to put my visual images next to their hypothetical descriptions.

‘THE CURVE OF YOUR EYES GOES AROUND MY HEART.’

—PAUL ELUARD

When speaking of calligraphy in this context, I use the term ‘image’ without the slightest hesitation. In my opinion, scripts stem from images. Ancient Sumerian and Egyptian writings were simplified images, as were the letters of the alphabet themselves at a later period. Calligraphy is but the quintessence of images, and we might ask ourselves of what kinds of images? Original images and not natural or photographic ones: images that emerge like signs, captivating the viewer’s sight and inspiring his mind.

Between 1972 and 1985, I participated in live performances with the French actor Guy Jacquet and the musician Fawzi Al-Aiedy. The actor recited poems in Arabic and French accompanied by the musician who played music and chanted the same poetic passages, while I created calligraphic scripts that were projected behind us onto a cinema screen. The spontaneity of this artwork proved immediately successful and further encouraged us to show continuous ingenuity and creativity.

Through the intense feelings that prevailed in the crowded halls where we performed, I found myself close to the music at times and to poetry at other times. My fluidly drawn shapes became the meeting point of several art forms, if we also include the voice of the actor and his expressive abilities. At moments, to keep pace with my colleagues, I would draw the letters so swiftly as to infringe upon the basic rules of calligraphy with regards to speed. But, in spite of the rapidity of pace, I always managed to keep in mind the fundamental aesthetics of Arabic calligraphy.

Creating calligraphy in front of the watchful eyes of spectators and under different emotional states generated new challenges every time. The spotlight directed towards us, so that the public could see us from the dark recesses of the hall, was more like a burning sun for the eyes, and I had to face unexpected events with both physical and mental skills whenever I would draw my scripts. In the midst of these struggles, crucial and unforeseen moments of great intensity would emerge from the vital fusion of these various arts.

After this experience of some twelve years, during which we staged dozens of cultural performances, I started introducing novel approaches into my calligraphy. During the performances, our poetry often dealt with subjects such as suffering and hope. My scripts featured a variety of situations such as the seasons of the year where the dark winter might be succeeded by a bright spring. My unfolding inscriptions began to be capable of illustrating such dramatic developments as they appeared before the public. Whenever our poetry reflected pain, I would use blunt, thick instruments that blocked the space and occluded the resulting structure. When the singer chanted with a voice charged with emotion, I would perform with slow and solemn gestures, and when his voice rose in anger my hands would accompany him with frantic haste.

‘IRAQ NOURISHED ME WITH LOVE FROM HER BREAST. BUT BAGHDAD SEDUCED ME WITH A SINGLE GLANCE.’

—IBN AL HASSAN MOUTRIF

I tried to provide classical Arabic calligraphy with a new form of articulation that was equivalent to theatrical or musical expression. Every week, I would isolate myself for hours in my workshop composing scripts on paper. I gradually began to notice the extent to which my calligraphies became influenced by my performances on stage, and I allowed these effects to become assimilated into my work. Little by little, larger letters formed, and dancing, modern strokes fashioned my writings to become an integral whole. However, these modernist strokes were always accompanied by ancient Kufic calligraphy, in tribute to the first Arabic script whose roots were similar to drawing. Today, this ancient precursor is represented by the horizontal line written beneath each flourish of scripts, rising like a colossal statue in the middle of the desert.

My modern scripts are thus clearly related to classical Arabic calligraphy, born as they were, from my long experience with calligraphers, though they also differ from it. After many years living abroad in another culture, if the person must certainly change, then so must his calligraphy also, which is but a reflection of the calligrapher’s life.

If we examine thoroughly all ancient calligraphy, we must notice that, in each century, Arabic calligraphy was marked by different variations and innovations. Likewise it also bears the unexpected influences of particular geographical areas. For example, one wonders whether the ancient Kufic calligrapher could accept the change introduced by other professionals working with bricks, referred to as ‘architectural Kufic calligraphy’?

I am certainly not advocating that all calligraphers should abandon traditional scripts in order to follow modern trends. I simply note that Arabic calligraphy needs to embrace various artistic movements. I often return to contemplate the heritage left to us by such celebrated calligraphers as Al-Amasi, Al-Hafiz Osman, Rakim and Hashem. I also value the new initiatives made by contemporary calligraphers in relation to classical calligraphy, when I encounter them in some Arab and Islamic countries.

‘Perfume’

I would also like to mention one of the poets who has influenced my calligraphy, namely Mansur Al-Hallaj (10th century) who creates with few words a musical composition filled with deep emotions. His unique poetic style overflowing with strong imagery is built on symmetrical structures. His marvelous verses enchant the ears as he says:

‘Her soul is mine and my soul is hers,

Her wishes are mine and my wishes are hers.’

His words, reflecting each other as though in a mirror, have inspired many calligraphers in the past and opened the path to a new calligraphic style which appears in the artwork ornamenting the Great Mosque of Bursa, in Turkey. However, the limpid stillness in the symmetry of his poems hides intense emotions and inclinations from within, which could have dangerous consequences for poetic calligraphy, like a boat caught in a sudden storm:

‘I float on oceans of passion, tossed about by waves,

Lifted up by moments and then falling back,

broken as I sink.’

Such a metaphor can’t be written in calligraphy independently of its author’s own feelings and spirit. Such a statement – what the heart reveals leads to knowledge – especially in this poem, embodies a simple meaning and rhythm. This kind of verse resembles calligraphy in its musical cadence and its overarching structure. Moreover, the words, whether heard or read, hide secrets that can only be interpreted according to each person’s individual awareness; and this helps explain the reason why these verses entered into the realm of art.

Below is another example of a poet who has inspired me in my calligraphies: Ibn Zaydún (11th century), who has left us a wonderful collection of poems based upon his political life. Yet the eternal aspect of his work is revealed through his love for the poetess Wallada, daughter of the Caliph Al-Mustakfi of Cordoba. The poems he wrote to her throughout his life confirm his great aesthetic abilities in structuring Arab poetry. In the face of suffering and loss, Ibn Zaydún concentrates all his sentiments towards artistic creation. Here he addresses the clouds in the sky:

‘Clouds charged with lightning, fly swiftly to her palace,

And flood her with all your benefits,

The one who flooded me with love and tenderness.’

This metaphor of Ibn Zaydún emerges from the depths of his heart. Here is a poet who has assimilated the heritage of ancient Arab literature. His poetic images are colourful and dynamic, and this is how he sends his words to Wallada on the wings of a breeze:

‘O morning breeze, carry my greetings to the one,

Who enlivens my day – though she lives far away.’

The poet’s broken heart finds relief in artistic creation, using spontaneous and sincere words, as he sees Wallada in all the aspects of nature.

Whenever I read Ibn Zaydún’s verses, I share with him his joys, pains and hopes, and images of natural landscapes pass in front of my mind’s eye. These visions find echoes in my scripts, reflecting the letters and the meaning of the words.

‘THE FLOWER OF OUR LIFE IS LIKE THE BLOOMING OF FLOWERS.’

—IBN ZAYDOUN

The question is often asked, how do words turn into a calligraphic composition? In the past, when a calligrapher wanted to render poetical writings, he would adopt a style such as the Thuluth, Diwani or Farsi scripts, and attempt to abide by the rules upon which all had agreed while drawing his calligraphies. His personal touch appeared in the dynamism and strength of his letters or in the introduction of new shapes, inspired by the style of ancient calligraphers.

When I am concerned with such calligraphic endeavours, I adopt a somewhat different approach. My scripts are largely dominated by the effects of landscapes and images. I always begin by imagining the poetic metaphor and wait for one word to prevail over the others so that I may enlarge that word and give it a distinctive form. I then calculate the number of straight and curved letters in order to produce a balanced structure. Then I allow my imagination to create various forms using these words and next I draw a quick sketch of the developing shape. I might modify the forms of letters that play only minor roles in the general structure or change their position within the word. For example, I could lift the letter ‘A’ at the beginning of the word in order to build the top of the new structure. While doing this, I keep in mind the virtual image of the poet and the overall meaning behind the words.

At first, the poetic figure generally seems quite ambiguous and some verses come into view faster than others. Sometimes a satisfactory resolution of these conditions might arrive from the very first day; other times only after a month of trying. This latter implies that I haven’t yet unlocked the mystery of the verse, and indicates that I need to pursue my exploration further.

'THERE IS A PLACE ON EARTH FOR EVERYONE’

—SCHILLER

Each letter goes beyond writing as it represents an artwork in itself. Moreover, a letter is charged with energy and should reflect two factors: strength and accuracy, and tranquillity and refinement. It ought to lay bare its own path, through a to-and-fro movement: rapidity and languour, stability and explosion.

The birth of new calligraphic scripts is in no way an easy matter, as the calligrapher needs to rebel against ancient calligraphic standards, breaking from them, before finally reconciling with them. At times, I feel that I am directly aligned with ancient calligraphy, at other times I feel totally opposed to it. I’m aware of the necessity of drawing inspiration from the heritage of ancient calligraphers, but at the same time I continually strive to explore the life that surrounds us, our role in the universe as well as our cultural responsibility towards society and humanity. The Chinese philosopher Confucius says of this matter: ‘One who doesn’t progress each day, falls behind each day.’

Setting up calligraphy instruments is of paramount importance. The ancient calligrapher used to prepare his pens and ink meticulously. For example, the qalam is thin compared to the size of my work, so I have created other instruments which enable me to draw strokes at the required width, with immediacy of execution. In 1978, I watched more than a hundred Japanese calligraphers producing calligraphies in public at the Sorbonne inParis. I saw them spread large papers on the floor and create swift, dancing strokes at lightning speeds with huge brushes that are similar in shape to large brooms. Since then, I have also tried to produce large calligraphic scripts as rapidly as possible, and as such, have created instruments capable of elaborating strokes in a single movement at the required width. While ancient Arabic calligraphy was composed using pens made of reed, all the large-scale calligraphies decorating the walls were produced and filled with delicate brushes. The largest instrument I have designed so far is 50 centimetres wide, whilst the largest paper on which I have drawn my calligraphies on the floor measured 3 x 5 metres.

Watching those Japanese calligraphers bore fruit several years later. The techniques of Japanese calligraphy added something new to the Arabic. However, the outcome of my work wasn’t related to the Japanese style at all. It was rather a modern Arabic calligraphy. The Japanese calligraphy has simply inspired me to draw large and quick strokes, giving full expression to feelings that were already inside me.

‘SAVE LIBERTY, LIBERTY SAVES THE REST.’

I produce most of my scripts with instruments made of thick cardboard or brushes, instruments similar to the tip of the common qalam used in the past, but up to ten times larger. I dip the instrument in colours, then pull it across the surface to draw letters that recall Arabic calligraphy in the manner in which the instrument renders curves on the paper. Some of these letters are analogous in shape to ancient letters, others have undergone changes. However, all of them have thick or thin shapes in accordance with the rules of classical Arabic calligraphy. I also keep in mind the preservation of the essence of Arabic calligraphy, conveying it visually through my artwork. I aim to improve and revive Arabic letters in the way change occurred throughout the long history of classical Arabic calligraphy; striving to open up new horizons in harmony with contemporary life, as, for instance, when I introduced calligraphy into the world of theatrical performance. I want my scripts to derive from classical Arabic calligraphy, yet retain their own specific characteristics. I also give great importance to the spaces in Arabic calligraphy; in other words, the empty areas bordering the letters. I imagine the calligraphic structure as a lonely tree standing in the centre of the desert, surrounded by boundless space.

We have all inherited many valuable aesthetic aspects from classical Arabic calligraphy, such as its elegant character, round shapes and linked letters which give the words the appearance of a perfect body enhanced by the measured proportions of length and width. In doing so, each calligrapher relies on his personal intuition, taste and culture. In modern calligraphy, we can benefit from this great legacy and can include such specificities of modern life as more recent information, and new cultural and scientific discoveries in the field of space. I attach special importance to the space behind calligraphies and imagine my calligraphic structures as statues rising into the sky, resisting both atmospheric pressure and the downward pull of the earth’s gravity.

‘EVEN MY SHADOW IS IN EXCELLENT HEALTH. FIRST MORNING OF SPRING.’

—KOBAYASHI ISSA

Most of all, I draw my inspiration from nature. I often feel my heart fill with sadness when I set eyes on a bent tree because it suggests a fall from grace. So then I shift to another tree proudly raising its branches towards the heavens. Then I return to my workplace attempting to illustrate this wonderful tree, and I design my letters by giving them the form of branches. Calligraphy is an art that reflects the essence of things, and not only that which the eye naturally perceives. Therefore, its complexity lies in the fact that it addresses the invisible, always exploring that fundamental nature behind the appearance of reality. To illustrate this we need simply to recall that the structure of a house represents the strength of its pillars and not the entire shape of its body.

Even though figures appear in my mind clearly and distinctly, it isn’t always that simple to put them down on paper, despite much preparation. Sometimes resin doesn’t work with coloured powder or the instrument becomes dry, preventing the calligraphic process. Conversely, at other times, after a long day of hard labour, indifferent and rebel strokes may begin to produce amazing shapes which appear quite unexpectedly – so free and elevated, large without being heavy, delicate yet unbreakable and finely proportioned. But then, when preparing to work on these calligraphies the next day, in the belief that I’ve discovered an impressive new style, the inspiration I felt previously, may have waned and I am forced to start all over again. Beauty comes and goes unexpectedly.

So, I resume my scripts from the start, sketching them, building poetic images in my mind, looking for a word that can soar without ever falling, seeking a dynamic movement that won’t degrade the overall structure. I allow colours to break through the forms of the letters and sense the vast horizon spreading beyond the flying letters of this massive word: a word that is simplified and abstract, yet rich in expression and images. Finding the right letters and spellings remains a crucial part of my artistic practice. Moreover, I am always under the impression that my expressive abilities are greatly influenced by the group of people to whom I belong.

‘IF YOU WANT TO HAVE FLOWERS, DON'T CUT THE ROOTS’

—JAPANESE PROVERB

Through the daily act of creating lasting calligraphy, my sole objective is to recreate myself over and over again. Every attempt to improve, conceals a challenge to the improvement itself. Consequently, the architectural structure must stand firm, with no risk of falling. If I am unable to achieve this balance in the calligraphy of the upper word, then I have failed; meaning that I must begin the entire process again. However, in this process, my own limitations as a person and my lack of inner balance on that particular day are brought to light. The experience of creating calligraphy thus leads me towards self-awareness, and might it not signal some form of improvement, if, whenever I stumble, I am able to rise again, to achieve more calligraphies?

Visual contradictions reflect those that are inherent in life itself and in our own lives as human beings. All these efforts reveal the desire to progress. No one can evolve without falling down once in a while. This should not be seen as failure. What we call failure is not the falling down, but the staying down, as Socrates said. Calligraphy helps to control the body’s energy and channel it towards precise movement. When words are soaring, elevated and light, one might fly along with them. Sometimes, perhaps for several moments at a time, the calligrapher becomes the master of himself.

‘TOWARDS ANOTHER LAND, A COUNTRY WHERE ONLY LIGHT REIGNS.’

—RUMI