Gesture & Mystery

Gesture & Mystery

Master Chinese artist Jin Weixin shares insights into the philosophical foundations of his art

in Weixin is one of the most celebrated and original artists working in China today. His creative output is breathtaking, both in it's sheer volume as well as it's stylistic depth—from innovative brush paintings to ethereal landscapes and epic sculptures, Weixin posseses a profound grasp of both traditional Chinese art as well as a mastery of Western drawing and scultpure.

in Weixin is one of the most celebrated and original artists working in China today. His creative output is breathtaking, both in it's sheer volume as well as it's stylistic depth—from innovative brush paintings to ethereal landscapes and epic sculptures, Weixin posseses a profound grasp of both traditional Chinese art as well as a mastery of Western drawing and scultpure.

In the article below he shares the story of his humble beginnings, journeys of discovery, and insights into the philosophical foundations of his art.

AWAKENINGS

Before I discovered I wanted to become a painter, as a young student in Fushun I used to sing in my middle school’s choir; one day as I was approaching the entrance to my school, I saw our art teacher painting a huge portrait of Chairman Mao. I was so struck when I saw this painting, and immediately told him I wanted to learn how to paint.

He replied, “Don’t you sing in the choir?” I said yes, but now I wanted to learn to paint instead. He then looked at me and said, “Show me your drawings tomorrow!” The next day I brought a painting to him I had made, depicting the famous Dragon Tiger Mountain. From that day forward, I studied painting.

At the beginning of my studies I was mainly taught how to draw geometric shapes, which I didn’t find very interesting… then one day I was assigned the task of creating a sculpture, and became immediately fascinated. I wanted to learn more, but since during the Cultural Revolution there were no plaster figures available in art supply stores, I decided to make one myself.

In those days I knew there were large amounts of mud in the open-pit coal mines in my neighborhood, so I rode my rickety bicycle to a nearby mine, gathered some mud, placed it in a noodle bag and brought it home on my bicycle.

The sculpture I created with this mud was bigger than a real-life person. After it was finished I painted it white, and remember fantasizing that it was made by the ancient Greeks. I placed it on a table in our home and lit it with a lamp, being careful to shield the glare with a shade so as not to disturb the sleep of my siblings.

The next day when I presented this work to my teacher he was impressed. I found the other students in my class were now far behind me in their progress, mainly because while they were playing outside, I was always at home painting.

Before long my teacher decided to introduce me to the City Art Training center, where I connected with more student artists. Shortly thereafter I went to the countryside where I continued to paint. The peasants there modeled for me, and I improved a lot during this time.

Then on January 8th, 1976, China’s head of government Premier Zhou Enlai passed away. For us at the time it felt like the sky was falling… everyone was very sad and mournful. I wanted to draw a large portrait of Premier Zhou so that people could express their sorrow, so I referenced a photograph published in the People's Daily.

I had a large piece of paper but no pencil that was big enough to use, so I created one by burning my own charcoal on our stove. I drew the portrait and my brigade held a memorial where everyone bowed to the drawing, crying and expressing their feelings. That day I recognized the true emotional power of art, and made the decision to completely dedicate myself to the path of the artist.

After this experience I became very famous in my village. I stopped doing other forms of work and engaged in art-making full time. I painted a lot of migrant workers who went to work during the day and came back at night, and my painting abilities continued to improve very quickly.

In 1979 I was admitted to the sculpture department at the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts; on the day I received my acceptance letter I jumped with excitement, as I knew my fate as an artist was sealed.

THE ARTIST’S JOURNEY

Studying sculpture at Lu Xun Academy helped me develop and cultivate a deep understanding of the structure and anatomy of the human body, providing a strong foundation for my future painting and sculptural work.

At the Academy I learned about the great Western artists Rodin and Michelangelo, and in class I constantly used an album of Michelangelo's drawings as a reference. I admired Michelangelo so much that I soon found the musculature of my sculptures were extremely similar to those of his own. My sculptures had completely lost their individuality! After having this realization, I began to think about how I could cultivate and convey my own unique artistic personality.

Drawings of Michelangelo

One of my graduation requirements was to create a final sculpture. For the theme of this work I chose to return to my hometown and visit the local coal mines once again. This time I observed and sketched the people at the mine day and night, creating a sculpture that captured a momentary snapshot of the daily life working at the mine.

In the front of the sculpture I depicted a worker on his way to the mine, and in back I included another man whistling and carrying a lunch box. The sculpture has a strong sense of form, and I wanted to emphasize the smell and shape of the mud. This work was featured in my graduation exhibition, and caused quite a stir in the school.

My tutor told me Mr. Wei Lianfu, a famous teacher from the oil painting department, had come to see it five times. This made me very happy, and later the sculpture was featured in the Sixth National Art Exhibition of China, where it received an Outstanding Work Award. This positive recognition gave me great confidence in my art, and encouraged me to continue to pursue my path as an artist.

Sculpture of workers at the mine

After college I then attended a planning and design institute in China where I had my own studio, and began creating large-scale urban sculptures. On the bank of the Hun River I created a large bronze statue of the national hero Yang Jingyu, a sculpture of the mother and child Qiaotou of Xinhua, and others.

However, soon after this the ever-growing urban expansion that was happening in China at the time resulted in more city roads and fewer available green spaces to display such sculptures, causing my urban sculpture career to decline.

Soon people stopped investing in urban sculptures altogether, and so I put down my sculpture knife and began creating Chinese paintings. I realized that unlike urban sculpture, there was no need to find the support of an investor before creating a painting, and as oil painting wasn’t an option for me since I didn’t have the proper setup, I found traditional Chinese ink paintings were much easier to create and sell, because they didn’t need to be mounted.

I began working everyday on my own in a large office, locking the door behind me and painting late into the night; it was during this period of solitude that I developed the foundation for my unique style.

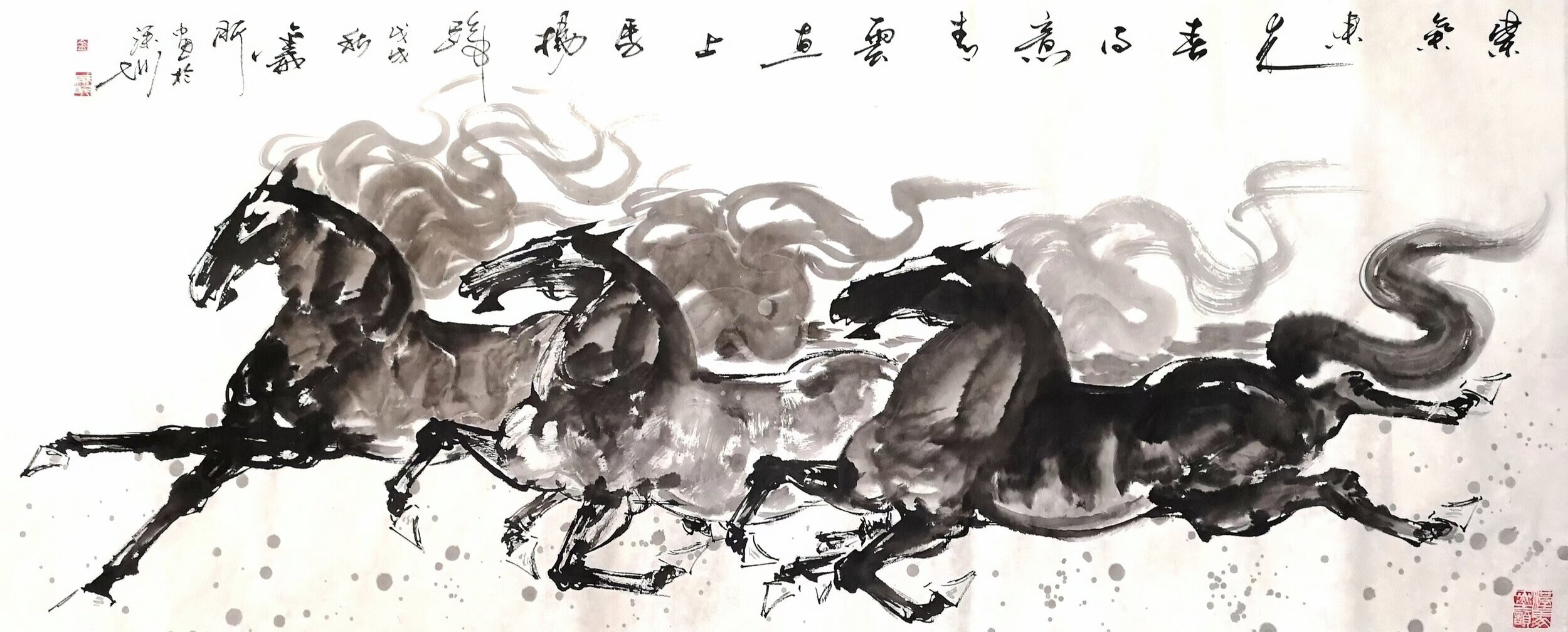

I began to create a wide range of paintings, for many of which I chose to focus on the theme of horses.

Given my background in sculpture, which gave me a strong understanding of anatomy, I found I was able to draw horses with great naturalness and fluidity. I started to use more water in my brush strokes, creating very bold lines and really allowing the ink to shine, so that the horse's form and structure was dynamically displayed.

I also used gestural strokes to invoke a sense of wind, particularly through the horse's mane and tail, creating a musical and dance-like quality. Over time many people started collecting my horse paintings, and the governor even gave one of my pieces to a foreign politician as a gift.

Combining my understanding of sculpture with the expressive qualities of my brushwork, I developed a distinctive approach to depicting the form and structure of my subject. This approach differs from a traditional Chinese painter’s in part because of the influence of these sculptural and spatial elements.

I think in turn it’s also uncommon for sculptors to incorporate an understanding of painting into their sculptural process, which I bring to my work as a result of my multi-faceted approach.

In addition to the more experimental and innovative elements of my painting, I of course owe a tremendous amount of debt to the great masters of the past.

In traditional Chinese painting there are different ways to make full use of the saturation of ink in water, so that each painting can achieve a mysterious and nuanced expression. Applying these techniques to my own works, I also create more traditional paintings depicting flowers, animals and other natural phenomenon.

Studying the works of artists such as Huang Gongwang, Liang Kai, Xu Wei, Wu Changshuo, Qi Baishi, Pan Tianshou and Ren Bonian, as well as the landscapes of Fu Baoshi, Shilu and Li Xiongca, I have learned immensely from their use of ink, space, color and so on.

I’ve also visited museums and exhibitions around the world to learn from the works of great Western masters such as Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Picasso and others, who have had a significant impact on my approach to painting as well.

INVOKING MYSTERY

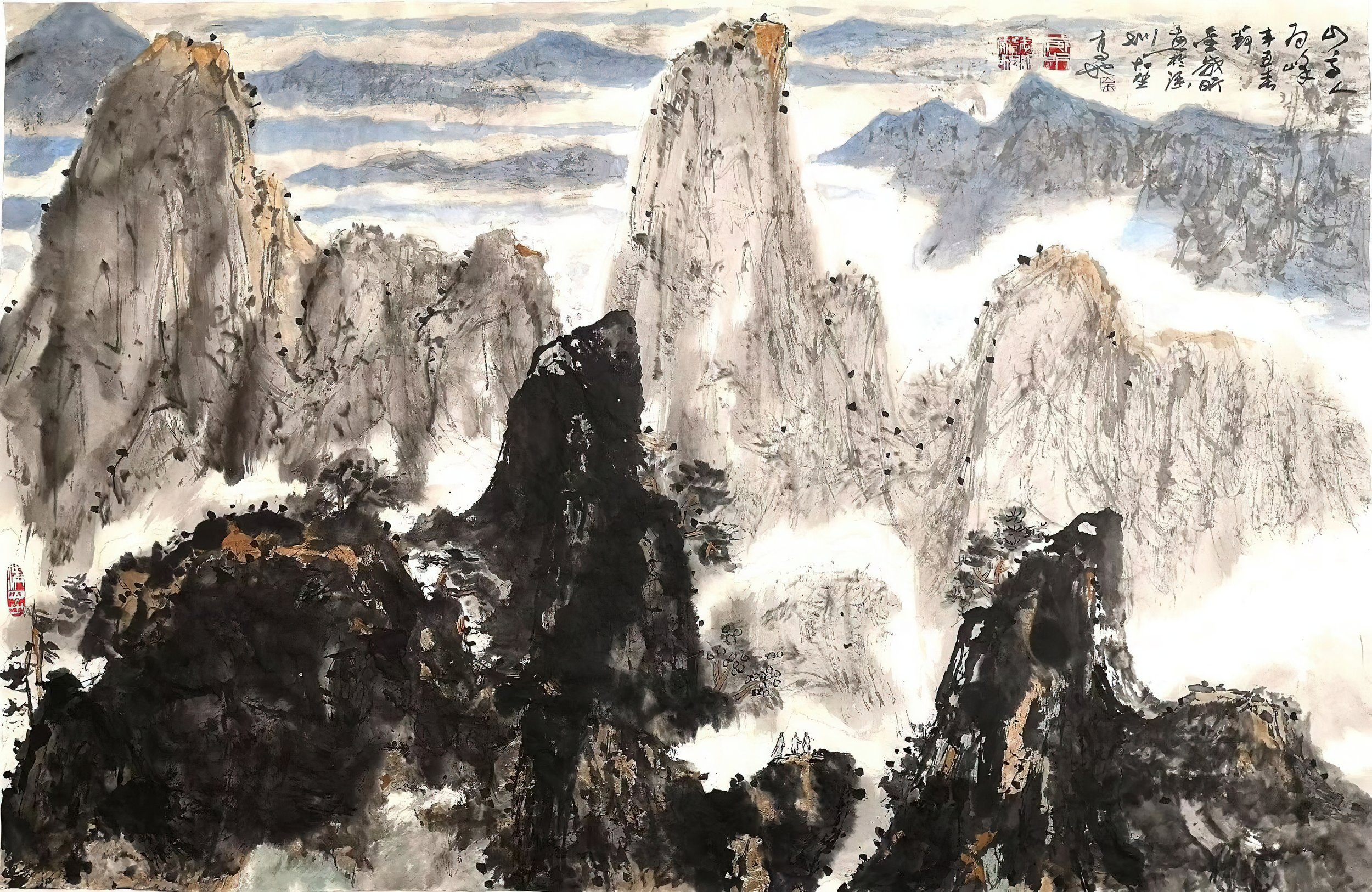

Another example of how I have combined traditional Chinese painting techniques with my own imagination is through my approach to abstract landscapes.

When I paint a landscape, the world I create is a mystery—it is a space that does not yet exist in this world. My task as a painter is to boil down this mysterious creation into something the average person can connect with and understand. In doing so, I’ll often include some form of narrative that people can relate to.

For instance, I’ll add ponies or people to the landscape to define the spatial elements of the painting, articulating the relationship between humans and animals, while also being careful not to shift the viewer’s attention away from the underlying atmosphere of mystery the painting represents.

To achieve this I approach each canvas as a space of pregnant emptiness, wherein an infinite number of artistic possibilities can spring forth, revealing a mysterious and ever-changing world that activates the viewer’s imagination.

If I’m successful, my brush and ink create an unbounded world. On the other hand, if I limit my thinking to replicating a landscape that already exists, I let go of the possibility of creating a world that no one has yet imagined.

The principles that inform this approach to creative work have deep roots within the Taoist philosophies of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu. In my paintings there is an artistic language akin to that of Tai Chi, which is very suspended. When you look at them you will feel a sense of rotation; as if time and space are colliding.

I feel that painters have a special responsibility to use art to reveal the mysteries of existence in this way. When I see the world, I use my own vision and touch to express the mysterious nature of reality through my art, which is then received through the eyes of the viewer.

Lao Tzu said the Tao comes from and returns to the Tao, the source of all manifestation. In this way all form and expression effortlessly flows from nothing, and returns to nothing. This philosophical ideal permeates my total approach to art.

No matter what style of painting I create, when I look at a blank piece of paper, I first ask, '“What do I want to draw? How do I draw it?” I think about these questions. Once I decide where to begin, I start using my brushes to articulate the overall structure and layout of the painting.

Then my brush and ink engage in a dynamic conversation through the use of small and large strokes. Here I am aware of the underlying limits and scope of the painting, while simultaneously finding freedom within these limits through my use of water and ink on the canvas.

Some of my paintings tell stories; I may paint mountains, rivers, wilderness, sunshine, rain dew, or a vast sky. I paint to guide my viewers into the worlds I represent, and become acquainted with the unique language of painting.

I believe anytime you stand in front of a truly great work of art and reflect on what you’re seeing, in that moment you can intuit the origin of all art. Experiences like this give you creativity, and expand your imagination.

When I look at such paintings, I feel inspiration for my own painting practice. I fill my paintings with the will to stimulate every artistic nerve, and my paintbrush serves as a tool to articulate the spaces that people see (and cannot see). I believe this is how great artists interpret and give life to their inner world through their creative imagination.

Through the act of painting I experience a meditative enjoyment of beauty; and I believe it is this process of the enjoyment of beauty that reveals the true power of art.

In traditional Chinese painting, the categories of painting are very defined— some artists exclusively paint landscapes or flowers and birds… other artists are exclusively focused on calligraphy. However I do not want to limit my art to only one medium or style; I'd like to incorporate all kinds of imagery in my paintings, including calligraphy.

I’m willing to express the world of all things and all beings through my paintings. This is a very difficult thing to do, but utilizing the philosophy I’ve developed, I'm willing to use my painting knowledge to transcend these limitations.

In early 2020, I began a project where I painted 100 historical figures of China. I included figures from the pre-Qin period (2nd Century BC) all the way to the Qing Dynasty (17th Century AD). I wanted to paint every subject in the most historically-accurate way, which required a fair amount of research into the characteristics of each time period in order to offer an authentic experience.

I included Li Bai, Xu Wei, Liang Kaiwen, Zhengming, Du Fu, and others. Through this project I wanted to reveal the epitome of ancient Chinese civilization, and provide a relatable artistic means for viewers to connect with China’s historical evolution. The project exhausted me for over a year!

Some of the works from this series have been published by China's mainstream media, and the response among the public has been very strong. Viewers were inspired to have the opportunity to feel and experience the wholeness of Chinese civilization through these works.

Several years back in 2014, I remember I had a solo exhibition in Los Angeles that was well-attended by fellow artists and Hollywood types. I didn't expect the attendees to relate to my paintings, yet one of the producers took my hand after viewing the exhibition and told me she was very moved by my work, and was a big fan of mine.

To me experiences like this affirm my belief that art is the language of the world, and can be shared and passed on to people from many different backgrounds and languages.

Moving forward, through my art I want to continue to hold the reins of Chinese history tightly, and hope to help people all over the world better appreciate and understand China’s unique 5,000 year-old cultural and artistic heritage.

This is my understanding of painting and how I feel about my art. I strongly believe that it is my life-long duty and responsibility to help Chinese art continue to flourish, and become a great source of inspiration for people all throughout the world.

— View Jin Weixin’s available works here —