Living Traditions

Living Traditions

A unique school demonstrates how timeless crafts bring greater meaning and harmony to our lives.

The Prince's School of Traditional Arts is one of the few higher learning institutions in the world dedicated to the in depth study and practice of traditional arts and crafts, with an emphasis on how these timeless forms may serve as a means to create greater harmony in our lives and the world around us. We recently visited the school's East London headquarters to speak with Director Khaled Azzam, and learn more about their ethos and educational offerings.

A TOUR OF THE PRINCE'S SCHOOL OF TRADITIONAL ARTS.— film by Ian Skelly

A NATURAL ORDER

Can you speak a little about the underlying philosophy of your school?

We are called the School of Traditional Arts, and the word 'tradition' is in fact very important for us.

Tradition can be thought of in different ways, perhaps the most common being the historical customs or mannerisms of various cultures from the past. Yet if we inquire more deeply into the meaning of tradition, following it all the way back to its source, we come to what the Buddhists would call 'the right way of living', or the natural order of things.

This order may appear to us through a particular pattern or encounter in our daily lives ...a flower, a piece of music... a glimpse of something that awakens a sense of harmony or beauty within us. It's very difficult to define precisely what this experience of beauty is, but it seems to act as a gateway; a moment that catches our attention, and opens us to the greater reality of who and what we are.

We understand the traditional arts to be manifestations of this natural order, which is in a state of continual renewal, always bringing forth new and interesting forms into the world, because it is alive.

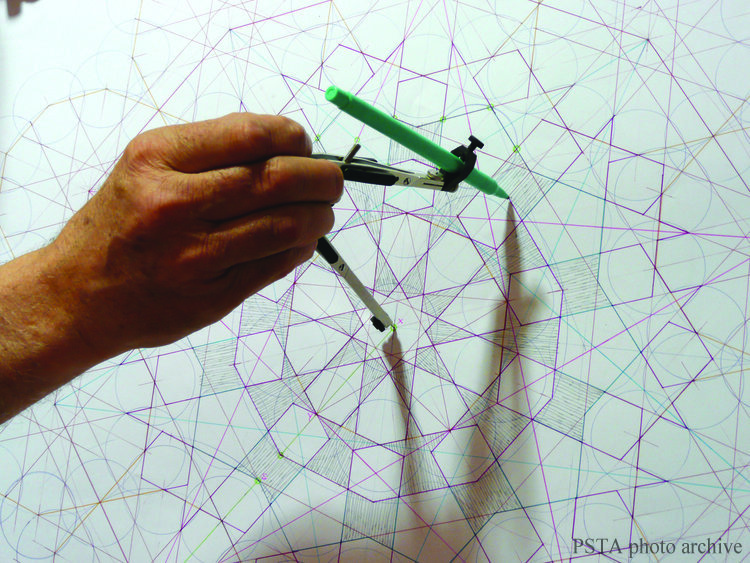

We help our students develop a sense of this order through exploring the geometric symmetries and patterns found within nature: how the stars move, the cycles of the seasons, what makes the flowers grow, our DNA structures...

As they discover there are common principles that create order in the natural world, they realize they too are part of this order; that everything we experience and do in our day to day lives comes from these deeper structures and patterns, and although we're not normally conscious of them, they make everything around us work in harmony.

How does this approach to education differ from what one might be taught at most contemporary art or design schools today?

Today in many art colleges there's a lot of pressure for students to be original—you have to be clever, you have to be different and unique... and some people thrive on this, and some people do not. In my own experience I did not, as I felt I wasn't there to be told to be original but to acquire knowledge, and the teachers were there to teach me this knowledge. Why else would I be there, if I already knew what I was doing?

So at our school we’ve come to redefine the idea of what it means to be original, and realize we are in fact doing original work because it has an origin. And more than that, it has a common origin.

Meaning that if your work is original, I can trace a path back to its origin, which is my origin too. In this way I'm able to relate to your work not just on the surface but on a deeper, more universal level, and this creates a resonance that links us to one another, to nature, and to the greater tradition of humanity.

Understanding this connects us to a sense of the timeless; it develops our sensitivity to the processes of time and space and unity, and therefore everything we do and everything we think about can begin to become an expression of this consciousness. We strongly encourage our students to contemplate and reflect on all of this.

Then when I walk into a Gothic cathedral or a Buddhist temple, I understand what these people did. I feel something that resonates, that brings me into contact with this higher level of order, which is the inspirational or spiritual dimension from out of which all these things come.

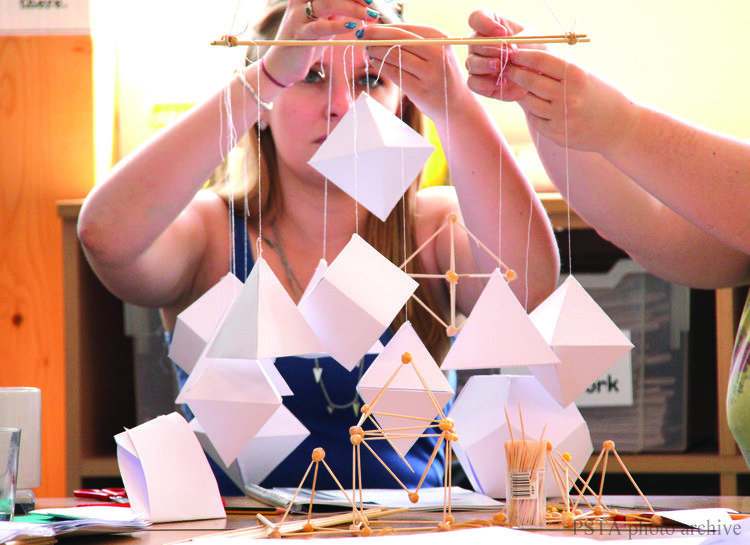

At the same time we are also not just talking about philosophy, or simply having discussions. This can be good to open things up, but then we need to get up and do some geometry to actually see how unity manifests itself, how all of these different shapes emerge from this unity, and then return to it.

CRAFTSMANSHIP

Then when it comes to learning the crafts, we use the same approach. When teaching painting for example, we first ask our students ‘what is color, and where does it come from?’ We show them that it comes from the earth, from the clay, the same as where we come from. In this way everything we do is seen as a process of alchemy—of drawing raw materials from this basic nature, and transforming them into art.

We help our students understand that craftsmanship is not a product, but a process—the process of finding the right way to do something.

For example I’m an architect, and I’ve learned that whenever I'm starting a new work, I project images in my mind about the expectations or ideas of what I think this work should be—and part of my nature is to chase these expectations, to say to myself ‘this is what I am going to do’.

Yet these images can be deceptive, because if I'm walking this creative path and am also chasing these images and expectations in my mind, they may not be right —perhaps sometimes they might be— but they can also lead me away from following the living energy of the moment.

But if I look at these images and say 'thank you, I will put you aside now, and begin the process that is in front of me', then I trust I will naturally come upon the right result. And learning to appreciate that process, that is craftsmanship, that is what we try to teach our students. Because if you only understand how to pursue one image and one result, you will be limited; but if you learn to let the process guide you, you will become truly creative.

And then creativity and craft can become one.

Yes, and this is where the crafts can go wrong, because we meet a lot of craftsmen from all around the world —and we of course have great respect for them— but sometimes they hold so closely to the idea of their work ...I’m the 8th generation and so on... that they end up repeating the same mistakes their grandfathers did, because they're simply copying what came before, and not allowing any new energy or creativity to enter their work.

Then people grow tired of seeing the same things being made over and over again, and the craft becomes disconnected from the living culture, because it’s no longer relevant; it’s no longer a living tradition. This is why I often ask my colleagues, 'why did modernism happen?' There was a reason—because people like us got lazy, people like us began to simply copy forms.

Then others came along and realized 'all of these are just empty forms, they're no longer relevant or real to us, so let’s just scrap the whole thing and start again.'

So the crafts are not dying because people do not know how to do them —it is not difficult to learn the crafts— they are dying because we don't know why we are doing them.

Which is why it's so important to be open to new things, to be willing to make mistakes, and trust the process...

Exactly, trusting the process, and seeing what comes out of it. I was in Jeddah a couple weeks ago where we have a center (The Jameel House of Traditional Arts), and we were starting a new geometry class. There was a woman in the back who was having a difficult time, so I went over and had a chat with her. I asked her how she was doing, and she said ‘I’m struggling, I can’t get this pattern to work. I’ve tried several times but I can’t do this...’

I told her this is not about the pattern—the pattern you will eventually learn; maybe it will take 10 times, maybe 20, but you will learn it. This is about the struggle that is inside you, and learning how to deal with that struggle, how to find a way to understand and resolve things by learning patience, calmness, and clarity.

The Jameel House of Traditional Arts.—Excerpts from a film by Ian Skelly

I think many people today are struggling to find this same state of calmness and clarity within themselves, yet don't often associate this with the process of a discipline, or a craft...

Yes, for us it comes through doing the work. We do it day in and day out; it's very disciplined, very challenging, and only those who want to go further will. Having done this for a long time, we can now usually tell early on who will continue and who will not.

That is the first test, learning how to take this on, how to do the work and move forward. Then you are on the path, and what happens happens. There are no expectations, as your expectations are illusions as well.

So the work is an offering you make of yourself; a selfless offering made with the best of intentions. And in those moments when you feel stuck, if you learn to trust the process and persist, eventually the obstacle will lift, and you might see something. And those are the moments when everything becomes worthwhile.

PERFECT TECHNIQUE

When I was a student there was this brilliant architect I worked for—he was really tough on me, but I was always very willing to learn from him. However one day I lost my composure and said to him ‘why does it always have to be so difficult?’ He turned to me and said, 'because I see something in you, and all I want to teach you is perfect technique every time.'

'Someday you will see something that is beyond you,' he said, 'and at that moment, if you don’t have that perfect technique to bring it through, you will remain frustrated.'

He spoke of the 'frustrated artist', and asked ‘why are they so frustrated?’ Because they have the capacity to see something in their imagination, but when it comes through them, it’s not what they envisioned. They haven't perfected their technique, so they cannot truly bring their potential to fruition.

They can feel that lack... 'I can see it, so why can I not create it?' As an artist this can drive you crazy, you know maybe make you want to cut off your ear!

This simple idea brought tears to my eyes. I thought this man was so generous to teach in this way, because any moment might be that moment for you. I certainly know in my life the moments when I’ve done it right, and when I’ve done it wrong.

So this is the responsibility we have to our students, to support that clarity, that technique, that repetition, and the state of being that comes from this discipline.

DISCOVERING HARMONY

In addition to your offerings at the university and through your workshops, you've also created a course designed for children. What does this programme entail?

We've been working with primary school children for five or six years now, through what's called our Harmony Schools programme. When we began to design this curriculum we had all of these wonderful ideas, but soon discovered we needed to apply them in very practical ways—the course had to be relevant to teachers, because if it didn't fit into teaching plans and stages, we knew they would never do it.

So we created modules for the subjects of art, math, science, history and geography, and picked up strands across these subjects to show the interconnections between number, shape, biology, color, chemistry, etc. When we began to implement these programs, teachers started coming to us saying they'd never seen the children so focused, because they were never distracted or bored.

We've since come to realize this approach to learning is very relevant for them, because their mentality has changed since the more classical approach to education that's been taught in previous generations. Information now needs to be presented within a cross-curricular context, more holistically, and interestingly the children often understand this more than the teachers do.

So for us dropping down to this age group has been incredibly rewarding, because we're able to help children see the world for the first time through these eyes, and it makes such a profound difference.

And this programme is now being implemented in schools throughout the world?

Yes, we work anywhere where there is the need to; that is our commitment to education. We’ve worked with schools and locations across the US and Canada, in Azerbaijan, with some of the most deprived communities in Jamaica, with universities, wherever we can offer young people the opportunity to learn in this way.

THE TRADITION OF HUMANITY

Doing the type of work the PSTA is committed to must be both very meaningful and also a great challenge... where do you find the inspiration to carry this work forward?

Well there is so much happening today, and so many people are doing so many things—opening shops and closing shops, trying new ideas and concepts... and when you first begin something, you are just a part of these waves.

Yet if you last long enough, the curve begins to change. In the beginning I used to panic about the school. I thought 'oh god, if this dies in my hands...' and at the start of every year I used to say to myself 'if we just make it to the summer, it will be ok.'

This teaches you to appreciate every moment, and accept that any day may be your last chance... but the nice thing, and I think the encouragement that others should take away, is now that we've planted so many seeds, helped change so many minds, and created centers all around the world, I've realized this school has become a vehicle for a much greater process.

Now it’s not only about us, because if you hold on to this work long enough, you’ll begin to discover how much people really need it, and it will start to take on a momentum of its own.

I remember reading something a while ago that said when two masons and two craftsmen meet on a site to resolve a problem, they create a tradition, because that solution is going to continue. So when we do something together as a group, the result of that work defines us within the greater context of humanity, and that becomes a culture.

Over time we become part of something greater; we raise this work beyond just being in London or in Nigeria, and it becomes something shared by the whole world. Because what we are doing is very relevant; and through it we have to prove ourselves, we have to prove our integrity and our solidarity, and persevere for the sake of helping others, so that they too have the opportunity to participate in this living tradition.

— To learn more about the Prince's School of Traditional Arts, including their Academic and Outreach Programmes, please visit: www.princes-foundation.org —