The Beauty of Inefficiency

The Beauty of Inefficiency

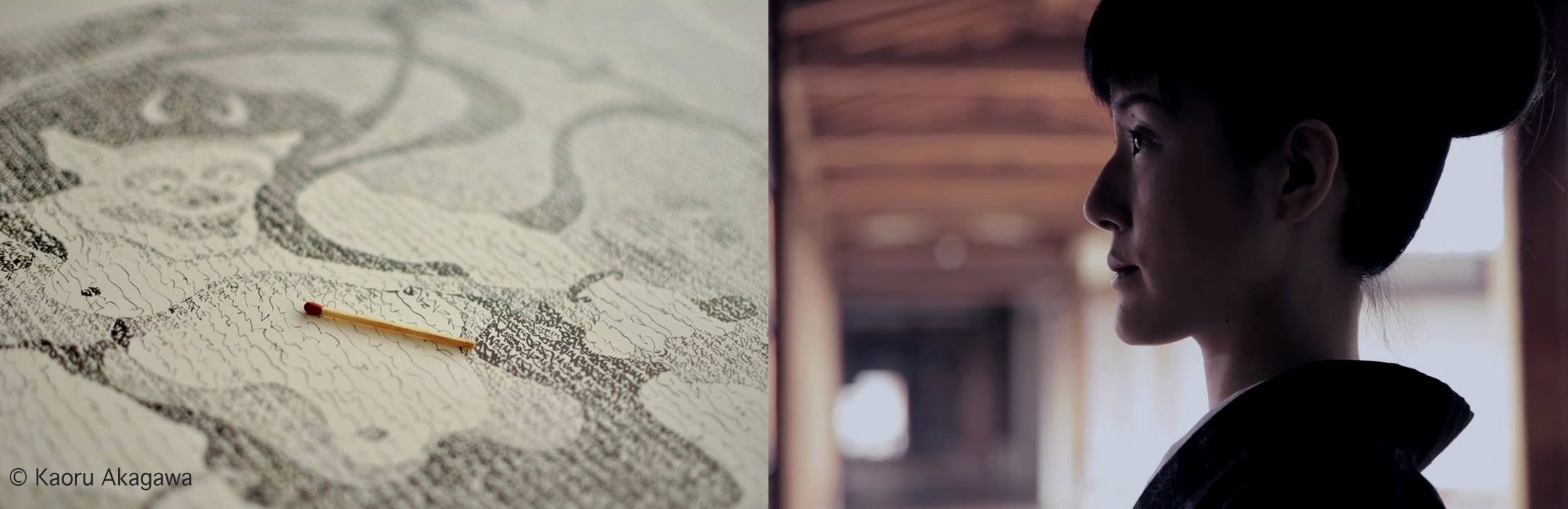

Discover the breathtaking artwork of master calligrapher Kaoru Akagawa.

Kaoru Akagawa is a calligrapher who specializes in the art of Kana, a rich and flowing style of Japanese syllabary. Here she tells the story of discovery that led not only to her mastery of this ancient craft, but also to the creation of a new and breathtaking art form that is uniquely her own.

SEARCHING FOR A SENSE OF PLACE

What was the journey like that led you to become a calligrapher?

Well I was born in Canada, and grew up in New York, where it became my dream to become an artist. However, it was actually quite difficult for the Japanese living there at the time, because Japan's economy was very strong, and some Japanese businesses had purchased significant real estate properties, such as Rockefeller Center, and people began to protest against this. Because of this I was often bullied in school by other students, who would tell me to go back to Japan.

So when I was 15 and my family did decide to move to Japan, I was somewhat relieved, thinking that since it was my mother country, I would finally feel like I fit in with the other people around me. But when I arrived, I found this wasn’t actually true, and realized that in many ways I wasn't really Japanese at all.

I noticed the way I thought, for example, was not the same as the other students. I wasn't inspired by my art education, because it was very rigid, and didn't allow for any kind of personal creativity. I found this to be very boring and frustrating, and very different from the art classes I had taken in New York. But I noticed that the other Japanese students, even if they felt similar to me, never spoke up about their feelings.

And so I realized that I was too assertive to live in Japan, and I began to feel kind of lost. I got confused about my roots, about whether I was really Japanese, and if not, who I really was... and eventually I gave up on my dream to become an artist.

DISCOVERIES

Then, after graduating from university, I started working as a graphic designer for TV commercials. And one day, while I was making these commercials, I suddenly realized that what I was doing didn't feel very genuine to me... it felt like a lie. I think I felt this way because I was making mostly cosmetic commercials, which felt very superficial and purely capitalistic to me. And also, because I was working with computers, where you can always change and cover up your mistakes by simply clicking a mouse.

And so I again became uninterested with what I was doing, and wanted to do something totally different, something real and genuine, where there was no second chance.

And I decided that was to write, with ink and paper and brush, because if you simply write in black ink on white paper, it stays there forever, and you can’t fix it. I really felt strongly that this was something I needed to do at that time.

And did you have any prior experience with calligraphy?

No, which is actually very unusual because in Japan, every elementary school student is required to take calligraphy lessons. But since I grew up in the States, and was now in my twenties, it was the first time in my life that I started to take lessons, and my master was so shocked, because my skill level was really like that of an elementary school child.

And so I was introduced to the two styles of Japanese calligraphy, Kana Shodo, which is the style that I work with today, and Kanji Shodo, which is the more commonly known style in Japan. At first I didn’t really know the difference between the two, so I started to take both.

But when I went to the Kana Shodo course, I was very surprised, because they were writing in Japanese characters that I didn’t even recognize. Afterwards, I went home and asked my parents if they could read these characters, and my father was like 'I've never seen this before, is this Japanese?'

And when I asked all my friends, still no one knew anything about these characters. So I decided to do my own research to find out.

I discovered that this style of writing was first developed and disseminated by aristocratic women in the 10th century, who were at that time restricted from writing in the more diplomatic and political style of Kanji Shodo, which was reserved for upper class men like samurai, monks and nobles.

KANA SCRIPT FROM TALE OF THE GENJI, EARLY 12TH CENTURY

So women of the nobility developed their own culture with Kana, which they used to communicate in daily life, and express their own unique personalities.

For example, they used Kana to write poems and love letters to their potential suitors, hoping to win over their hearts by writing in a rather soft and sexy form, in contrast to the dignified Kanji manner of the men.

It also became the writing style in which cultural and literary works were created, such as The Tale of the Genji, Japan's most famous classical novel, written by the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu in the 11th century.

Over time the noble class put much thought and effort into creating new variations of Kana characters in order to demonstrate their sophisticated intelligence, developing a unique style of writing that contained over 300 characters, and thousands of variations.

But then, in the year 1900, while the Meiji government was in the process of modernizing Japan, the complexity of the Kana system caused a perceived problem for literacy. So the government decided to limit the number of Kana characters taught in schools to only 50 symbols, naming them Gojuon, or '50 sounds'.

Additionally, the fact that Kana characters were often written connected to each other made it even more difficult for them to survive the process of modernization, because they were not properly suited to the new printing system.

While learning all of this, I suddenly remembered that when I was young, and my grandmother used to write letters to me, I could never read her handwriting, and used to request that she write more properly, using block-printed letters. And so I went and found one of her letters, and noticed for the first time in my life that she was actually using these traditional Kana characters in her letters, even today!

THE NAKASENDO HIGHWAY, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC STOCK

That must have been an amazing discovery! It sounds like at this point you really began to connect with the Kana style...

Yes, and around this same time, I began to walk an old trading route that connects Tokyo and Kyoto through the mountains, called the Nakasendo trail.

You can still follow this route today, and so I walked the whole path on foot, and discovered many old temples and castles along the way.

When I entered some of them, I was so surprised and fascinated, because with my new knowledge of Kana characters, I found that I could read for example, stories written in diaries from centuries ago within these temples and castles.

And also, as I was walking this path, I would come upon old characters written on memorial stones scattered along the trail, and of course all of these experiences made my growing enchantment with Kana Shodo even stronger.

PLUM BLOSSOM, KAROU AKAGAWA, POEM BY RYOKAN, 1758-1831

And so today, not many people in Japan are able to have these experiences you are describing, because they've lost the opportunity to develop full literacy in the Kana Shodo style.

Yes, my grandmother was part of the last generation that used the old Kana writing characters in their daily lives. By contrast, my father, who was born in 1936, the same year that Modern Times was released by Charlie Chaplin, didn't even know that this style of writing existed. Because, as Charlie Chaplin depicted in his film, anything inefficient was banned in "modern times".

But there are still some opportunities in daily life to see Kana characters in Japan, yet people don't pay attention to them, and don't even know that they're ancient Japanese characters. And when I tell them these stories, they are so surprised and shocked, and can't believe that they didn’t even know about them.

So you are reviving and carrying on this cultural tradition in your art, something which has basically fallen into obscurity due to the process of modernization... do you ever do any work to raise awareness about this?

Well yes, that’s one of the reasons why I created my own style of art, Kana Art, to raise awareness.

A NEW STYLE

What is Kana Art, and how did you come to create it?

Well, I am now living in Berlin, and when I arrived I wanted to show German audiences my Kana Shodo works. But I discovered that unfortunately, when most people in the West think about Japanese calligraphy, they imagine Kanji calligraphy, not Kana. So when they came to see my works, they often became confused, because they would be expecting more powerful and masculine types of characters, that resemble the zen-like style of Kanji calligraphy.

But my Kana is a soft, feminine, aristocratic style of writing. So they were like, 'what is this? Is this real, are you really a master of calligraphy?' I was so shocked that they responded in this way, and didn’t just simply find Kana calligraphy beautiful.

"When we learn to move beyond our familiar ways of seeing things,

and get to know each other's different points of view,

I feel this is one way to get rid of discrimination in the world."

And so I thought, I really need to do something about this, because in many ways, Kana calligraphy is actually more authentically Japanese than the style of Kanji. Kanji characters have their roots in Chinese calligraphy, and originally found their way to Japan through the importing of Chinese seals, religious texts, and other documents at the beginning of the common era. Whereas the characters of Kana Shodo were created in Japan, by people such as the noblewomen I have described.

Yet today in Japan, as well as the rest of the world, this is not really understood or recognized. And because of this, we are not able to honor and experience the beauty of our own cultural tradition. And so that is why I thought, I really need to do something about this, and show the world the beauty of Japanese Kana characters.

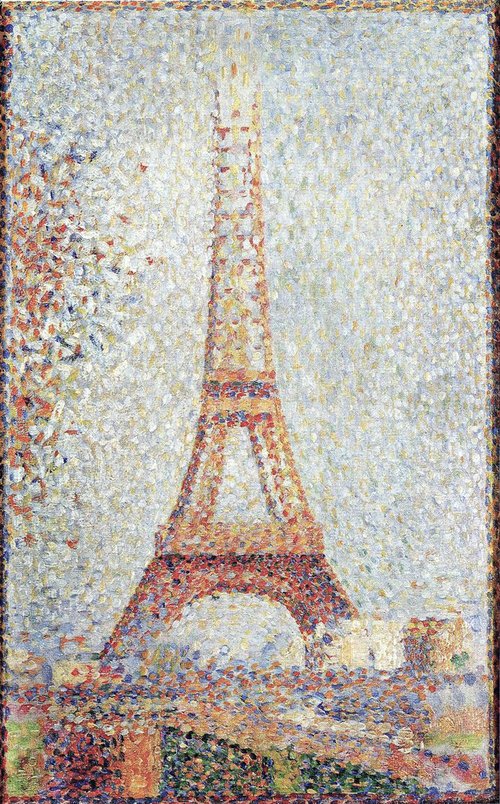

EIFEL TOWER, GEORGES SEURAT

Then I remembered a particular experience I had while attending the Opera, and had an idea. I remembered how when I used to go to the Metropolitan Opera as I child, the performers were always wearing costumes with period dresses, big wigs, etc., but when I came to Berlin, through the influence of German Regietheater, these same operas were performed within a much more modern context, in terms of the stage design, production, and costumes, without changing the original music or lyrics. And so I thought, if something traditional like opera can become modern, then so can Kana.

And then I thought of a painting I remembered seeing at the MET Museum in New York when I was nine years old. It was by an artist named Seurat, who painted using small colored dots —a style which is called pointillism— and I remembered this painting and thought, if he can paint with dots, then maybe I can paint with my Kana characters.

And so you decided to use Kana calligraphy to create larger types of imagery...

Yes— as I mentioned, Kana Shodo contains hundreds of characters, with many variations for each character. For example, below are some Kana characters that all represent the pronunciation "SHI". Only the simplest form of "SHI" on the very left hand side is still used in Japan today.

This is interesting, considering how in Western language, "A" is always "A", and can never be written with any other character or letter. But in Kana Shodo, there are no concrete rules for choosing which character to use to express the sound "SHI". So you may choose whichever "SHI" you wish, depending on the particular form and feeling you want to express.

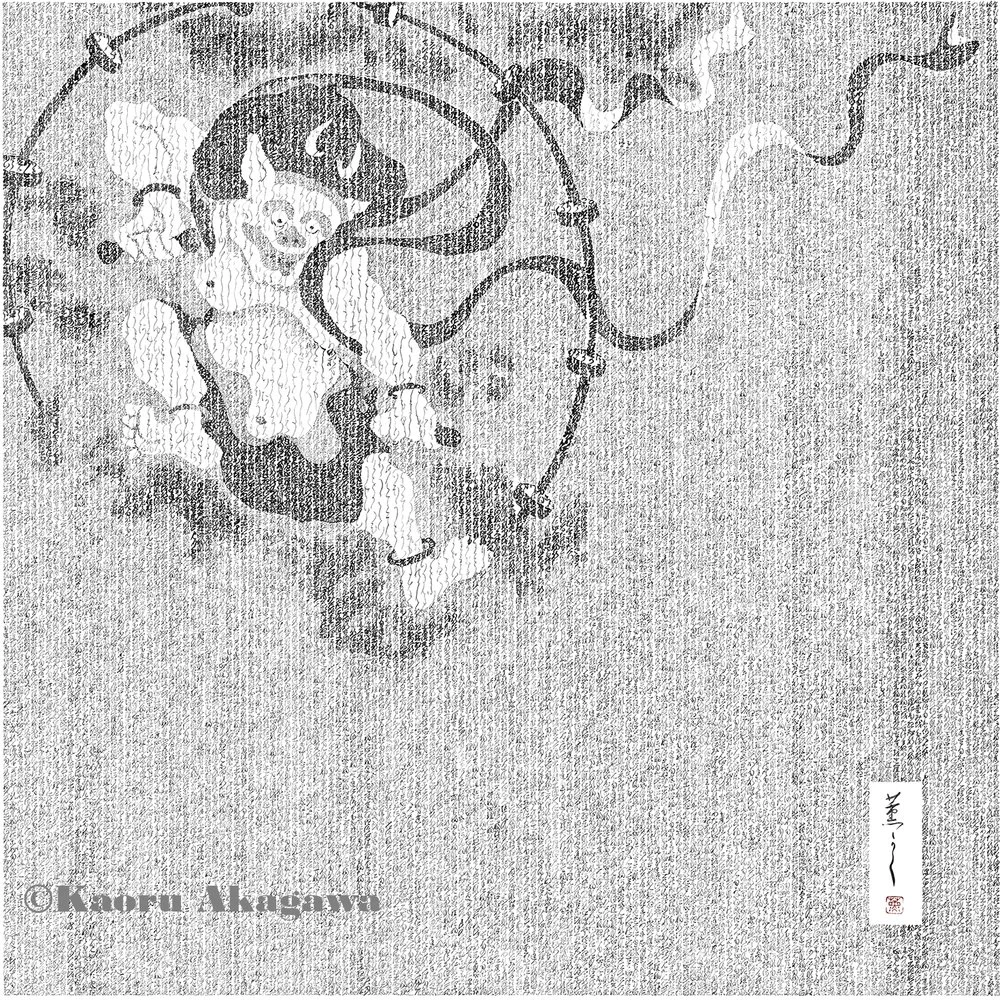

So in my Kana Art, I use this diversity in order to create contrast— in places where I want to make the image appear lighter, I use the simplest form of each character. And the places where I wish to make the work look darker, I use characters that contain more strokes, so they appear denser and darker.

BEYOND BORDERS

And how do you choose the subject matter for these works?

One aspect I always keep in my mind, is that I am interested in crossing the borders between traditional and modern, Western culture and Eastern, music and writing, and so on... because when we learn to move beyond our familiar ways of seeing things, and get to know each other's different points of view, I feel that is one way to get rid of discrimination in the world.

THE ROLE OF FALLEN LEAVES, TEXT FROM HAGAKURE, THE WARRIOR CODE OF THE SAMURAI

For example, when I used to be a child, I was often made fun of because I ate raw fish. Other children used to say to me 'ahh yucky, you eat raw fish!' As where today, when you go out to eat, there are sushi restaurants all over the place, and it's considered a quite normal and enjoyable form of cuisine.

And so when you learn about different cultures, and get to know them on a more personal level, such as by eating sushi, you don’t think it’s 'yucky' anymore.

In Germany, now there are so many refugees, and it's a huge social problem. But I think that maybe if the Germans learned more about the refugees, and the refugees learned more about German culture, they would learn to respect and appreciate one another, and accept each other more easily. And that’s something that I would like to help contribute to, through this kind of dialogue across different borders and perspectives.

That makes a lot of sense, taking into account how having grown up in different parts of the world, you've learned how to understand many different values and cultural points of view...

ONE HUNDERD THOUSAND YEARS OF FRIENDSHIP II, TEXT FROM THE DRAGON AND THE POET, KENJI MIYAZAWA

Yes, and not only beyond culture, but I am also interested in going beyond time. Because when I do an exhibition, I exhibit my new style, and at the same time I exhibit my traditional works alongside them.

In the beginning, I find audiences are not very interested in my traditional works, and have come mainly because they have been attracted to my more modern Kana Art.

But at the opening ceremony, when I begin to speak about the beauty of Kana characters, and the history behind them, they are very curious to see my traditional works, and become so interested that they even decide to purchase them.

So in my opinion, if I can integrate Kana Shodo into a modern context, and introduce people to it through my works, then I am also helping them to become more appreciative of traditional things as well. And that’s something I very much wish to do.

MOVEMENTS OF THE BODY

And also, music and writing— they look like two different things, but every time I go to a concert or opera, I am always so surprised how similar they can be.

For instance, when you want to play classical music, there are very specific notes you must follow, and you must play each piece according to these notes. But at the same time, you also put your own emotion into it, your own interpretation. And even if you don’t try to, your own mental and physical condition will always appear in the music.

And that’s exactly the same when I write something. If I'm writing a text, I may think I can just write it the same way every time, but my physical and mental condition always appears through my brush on the paper. And I can try to control it, but it will always appear just the same.

DEVIL'S LAUGHTER, INSPIRED BY NICOLO PAGANINI'S CAPRICE OP. 1 NO. 13

Yes, I see these correlations as well. For instance, when playing piano, if you are playing music that has more of a fluid texture to it, your hand will move more circularly across the keyboard —or more forcefully and angularly— depending on the energetic qualities you wish to express, just as in writing.

Yes, writing with the brush is really like music, and also like dancing. You have to have this rhythm in your body.

For example— just to draw a line, you can draw it straight, from dot to dot. But if you do this all time, it becomes very boring and monotonous.

But if you draw a line with movement, like dancing, then it's more interesting and more natural. It has more of a wave to it, like a dancing line, which is more dynamic, and more enjoyable; because everything is connected, dancing, music, writing... it's all the movement of the human body.

And just like in calligraphy, in music you don't have a second chance— you can always try again, but when you are performing, you don’t have a second chance.

So in this way music, just like calligraphy, is also inefficient. You start very young, and you practice every day for many hours, and this is really inefficient, but it's also really beautiful. And today you can produce music on computers, and can record and re-edit everything you make, but still, this inefficiency is really beautiful I think.

CROSSING TIME AND SPACE

Looking at your Kana Art, it appears the text you choose for your subject matter is always somehow related to the theme of the image you create. Can you say more about this?

Yes, for example, the original image featured in my work below is called The Great Wave by Katsushika Hokusai, which is a very famous Japanese wood print. And the text is from the opera The Flying Dutchman by Richard Wagner, which I have translated from German into Japanese Kana characters.

This opera begins with a scene of a storm on the ocean, just like the Hokusai wood print. I find it so interesting that Hokusai and Wagner found this image of a storm on the ocean so attractive, even though they lived so far away from each other, and in different periods of time. And because they were both so inspired by this natural form of the wave, I wanted to connect this and bring them together, because I find this coincidence so beautiful.

"Because everything is connected— dancing, music, writing...

it's all the movement of the human body"

BEYOND TIME AND SPACE, HOKUSAI MEETS RICHARD WAGNER, TEXT FROM THE FLYING DUTCHMAN

That’s wonderful— through this art you're revealing what are sometimes referred to as archetypes, fundamental symbols that all cultures and people resonate with and share... in this case, the elemental archetype of the wave and the storm...

And what about this next pair, what is happening here?

Well, this work is based on the masterpiece Fujin Raijin-zu by Tawaraya Sotatsu, which depicts the Japanese gods of thunder and wind. This work has actually been painted three times: first by Sotatsu in 17th century, and then later in the 18th and 19th centuries by two other famous artists who created their own versions based on Sotatsu's painting.

In 2006 I had the opportunity to attend an exhibition in Kyoto in which all three of these versions were shown together. Looking at them all side by side, I was astonished by how energetic Sotatsu's version was compared to the other two. I stood there for a long time observing them, and reflecting on what made this great difference, since the composition of all three was basically identical.

Then I noticed that Sotatsu didn’t draw the thunder god to exactly fit in the painting— the little drums surrounding him are partly not drawn, giving the effect as if he just swished onto the screen, bringing fresh air. On the contrary, the thunder gods from the other two artists were both drawn to fit completely within the screens.

FUJIN RAIJIN-ZU, TAWARAYA SOTATSU

At this time I hadn't yet discovered my own Kana Art style, but was beginning to feel the urge to create something new, and when I noticed how this tiny, tiny effect made such a big difference, this insight struck me almost like the thunder god himself— at that moment I swore to myself that I would never perfectly “fit in” to things either.

I then had another interesting thought, which was how Sotatsu's image for his thunder god was actually very similar to the depiction that Wagner had used for his own thunder god in his opera Das Rheingold. I thought to myself, why did these two artists, Sotatsu and Wagner, both depict the thunder god as a roaring male holding a hammer, rather than perhaps imagining this god to be a hysterical female, bursting out her anger?

And so this is why I chose the title Beyond Time and Space, and used the lyric from Das Rheingold to write Sotatsu's thunder god.

And regarding the second image, I didn't initially plan to create his companion, the wind god, but after finishing the thunder god, I felt that he needed his partner. So I chose Aesop's fable The North Wind and the Sun as my text.

When I was done with my two gods, I contacted Kennin-ji Temple in Kyoto, where the original Fujin Raijin-zu screens by Sotatsu are housed.

They found my work to bring ancient Kana characters into modern life very interesting, and approved me to shoot a film in the Kennin-ji Temple. It is normally quite difficult to get permission to shoot within the temple, but they showed great understanding towards me and my passion for Kana and Japanese culture.

THE ENDLESS GOAL

So how do you like living where you are at present, in Europe?

I actually find it really interesting, because Japan is basically one culture, and the US is also basically one culture, but Europe is so small, and yet it also is so diverse. You can drive one hour and cross a border into a very different culture, with completely different people, and after eight years of living here this is still so interesting for me.

And also, I get such different responses when I exhibit my works in different areas of Europe. When I exhibit my works in Germany for example, I always get so many questions, about my concept, my technique, and really at the end of the opening ceremony I’m always out of my voice because I receive so many questions!

DÉRIVE II, INSPIRED BY PIERRE BOULEZ

But in Paris, when I exhibited my works, they were not very curious about my technique or my concept at all, and no one asked me any questions, they looked and said ‘C'est poétique,' and that was it.

So I find it so interesting that Germans and French are so close together geographically, but are also so very different in how they perceive things. And I thought, that’s why French people are maybe more impressionistic, and Germans expressionistic.

And I am happy that I'm able to draw the attention of both audiences, and this year I will be holding a solo exhibition in Paris again, because last year was such a big success.

That's wonderful to hear, and what you say is also very interesting, as it reminds me in music of the difference between some of the more suggestive French composers such as Debussy, versus Bach or Beethoven and the German school, who represent a more explicit and systematic approach in their musical expression...

And the building up of motifs...

Yes exactly.

And I find it interesting that when I exhibit my works in Japan, Japanese audiences are actually more similar to the Germans than to the French.

I would actually be very curious to exhibit in New York one day, or anywhere in the US, because I am very interested to find out how American audiences would respond to my art.

You know I was never aware of it, but I think deep inside of me I was actually very affected by my elementary art school teacher in New York. I never asked him about it, but if I remember the things he told me about art, I have a feeling he might have been a big fan of Keith Haring.

Last summer there was an exhibition of his works in Munich, and I went to see it. There was a video of an interview with him, and in it he explained that in his childhood he learned to draw from his father, who told him not to draw disney characters, or other figures that already existed in life, but to create his own characters, using his own imagination.

And that's how he said he learned to be creative. And that was exactly what my elementary teacher in New York told me to do, to not just copy things, but to be creative.

That’s so interesting, because it sounds like when you went to Japan you had already developed exactly that kind of relationship to art, which would explain why you didn't find your traditional Japanese art classes very inspiring...

Yes, and even though I used to think that I didn't belong in New York while I was there, and that I didn't belong in the US, now I realize that this American spirit is actually inside me, and is one of my roots when I create something.

Whereas perhaps another root you possess could in fact be associated with traditional Japanese culture— the value of patience and discipline, or as you said inefficiency, which is something that is in fact often lacking here in America...

Yes, because to embody beauty and enjoy expressing yourself, you cannot ignore the basics. It's only through continuous practice and discipline that you're able to become free to express the passion and sorrow hidden within yourself... and this is my endless goal, to express my soul through the music and dance of my brush.