The Spirit of the Banjo

The Spirit of the Banjo

Chris Rippey reveals the neglected past of America's most misunderstood instrument.

Spirits

Can an inanimate object be said to have a spirit?

To most of our ancestors, from ancient times through recent generations, the answer would have been a simple yes. But, to we who live in this rational, scientific time, the belief in spirits or the sacred objects in which they might dwell would seem an indulgence of superstition at the expense of rational thinking.

And yet, closer inspection of our daily existence yields ample evidence that many, if not most of us, still regard numerous objects as being imbued with special power or meaning, if not spirit. I need not even mention the paraphernalia involved in religious sacraments to make this point, although the reader will surely have some idea of where that example might lead.

And yet, closer inspection of our daily existence yields ample evidence that many, if not most of us, still regard numerous objects as being imbued with special power or meaning, if not spirit. I need not even mention the paraphernalia involved in religious sacraments to make this point, although the reader will surely have some idea of where that example might lead.

For the purpose of this discussion, commonplace items will do just fine.

Consider if you will a watch. How might a pocket watch which belonged to, lets say, your deceased grandfather, differ in your regard from a similar watch which was manufactured in more recent times? Your grandfather's watch might not be made of gold, or even keep time anymore, whereas the new watch may be a shiny emblem of craftsmanship and horology.

But, odds are, your grandfathers watch would occupy a special place in your consciousness that the new watch could never fill. Perhaps your grandfather's watch was with him in the war - his good luck charm which, in his mind, helped bring him home safely. Perhaps he kept it until his death in old age as a potent reminder of his young life, in which many poignant memories and emotions were bound.

Would you, the watches inheritor, not be tempted to consider it a kind of lucky charm or talisman as well? Perhaps when you touched the tarnished surface, you would remember the smell your grandfathers pipe smoke or hear the sound of his voice in your mind. Perhaps, when you turned it over in your hands, you would somehow feel his presence around you in a way that memory alone could never evoke. Perhaps you would take it a step farther and even suspect that by merely holding the watch you might be absorbing something of your grandfather's inner experience.

What if this phenomena was not only related to his specific watch, but indeed any watch that fit the description more or less well enough? For instance, perhaps you do not inherit your grandfathers watch after all but, while perusing a flea market one day, you come across a watch lying on a shelf in some dusty corner stall; it is similar enough to your grandfather's that when you pick it up it evokes in you the same feelings, the same eerie sense of transcending the present and communing with the past.

This is but one of many possible examples which illustrate how we still have that fundamental impulse so freely indulged by our ancestors; that is to say, we treat objects more or less as if they have magic powers or connect us to spirits no longer embodied in the flesh.

CHINESE RITUAL ALTAR SET, 1046–771 B.C.

But really, what does the word spirit even mean? Does it represent a literal reality, an entity, energy or presence which might come to dwell within an object? Or is spirit but a metaphor, one which we invented to encapsulate our subjective experience – the emotions, memories, and sensory impressions brought to mind when we interact with an object or place?

While ancient humanity was quite comfortable with the former explanation, most of us living today see ourselves as believing at least mostly in the latter, despite our contradictory behavior when no one is looking.

But, regardless of where one might stand concerning the literal reality of spirits, one thing is for certain. Every object does indeed have a story behind it which, if looked into deeply enough, can profoundly alter how we perceive that object, or indeed any resembling it. Could they but speak to us, many of even the most commonplace items with which we are surrounded would tell us stories of survival, innovation, struggle, passion and bloodshed; such that we might, knowing these stories, never again be able to regard these items as merely commonplace.

And there are some whole classes of object behind which these stories are so unexpected, so stirring to the emotions and the imagination, and so deeply connected to our effort to make meaning of our life, that it is impossible to interact with any representative of that class of object without awakening in us some strong inner feeling. These items, in reality or metaphor, are those which stand out as having a spirit.

To me, one such object, unlikely as it may sound, is the banjo. Let me explain...

When I received my first banjo as a gift from my father-in-law, I hadn't the foggiest notion that this Southern folk instrument could have any important historical or symbolic meaning - especially to me, a non-Southerner with no particular interest in or love of Bluegrass music. What I did know was that, thanks to players like Bela Fleck, the banjo was breaking free of stereotypes and beginning to enjoy more popularity, crossing genres and redefining its limits.

So, when I first picked it up, it was to me little more than a slightly odd stringed instrument, ready to be experimented upon and taken in any musical direction - which is just what I did. I composed music for it, learned how to incorporate that funny short string into my playing, and more or less treated it like a funky, tinny-sounding guitar; a tool for my own self expression.

And yet, in time a strange sensation came over me. Though my first compositions worked splendidly, it was now as if the banjo was resisting me. Despite my increasing command of technique, the instrument didn't seem to want to convey the kind of musical emotion I was asking it to - it didn't want to sing in my voice and my voice alone. It had its own voice, one with which I began to struggle as I wrote song after song that somehow just didn't work. At intervals I would become disgusted that, to a degree I had never encountered in any other instrument, the banjo did not reward my efforts of musical exploration, and I would quit playing it for months at a time.

And yet I always felt a magnetic pull to try again, to understand the alluring undercurrent of darkness and romance that I began to sense inside of this, the brightest of instruments. I began to feel that, despite its ubiquity in America, the banjo had a foreignness to it, an uncompromising stridency of timbre and nakedness of emotion that one might only otherwise encounter in the folk music of an isolated, old-world village.

And I began to feel that, despite what people were always telling me - i.e. that the banjo is the happiest of all instruments, and therefore one cannot hear it without becoming happy oneself - the banjo nevertheless seemed to posses a kind of mystical gravity, a sacred solemnity utterly at odds with its reputation.

Naturally I began to look for where this feeling might be coming from. I listened to old recordings, watched old videos, and read recently emerging writings and research about banjo history.

The story that began to emerge, and is indeed still emerging from this inquiry into the past, is part of what I am going to tell you now, that you might understand the spirit of the banjo in a different light. This understanding, I must point out, is not a definitive history or presentation of absolute fact, but is the point of view of someone who has a loving and difficult relationship with an instrument that has an enigmatic spirit of its own.

So, let's start at the beginning. Not, as you might suspect, at the birth of the banjo itself - which, as it might seem at first glance, took place only a few hundred years or so ago - but at the beginning of all music. For the banjo, as we will soon see, has a spirit much more ancient than it's body.

THE BEGINNING

Since the beginning, people have created songs to be sung at almost every occasion of life. Songs to help us work, songs to help our children sleep. Songs to express our feelings, soothe our souls, and carry our prayers. Songs for dance and ritual - ecstasy and healing, songs to call back lost souls, banish sickness and evil, and even to help us leave our bodies or connect with our ancestors in the realm of the spirit.

Yet in the beginning there was only the sung melody, woven through time by the rhythm of hands and feet striking against themselves, the ground, the animal skin drum. In time we began to construct musical instruments, of which many thousands of unique specimens eventually proliferated, each of them singing in voices deeply connected to the source of their origin – the human relationship to nature and the cosmos.

BONE FLUTES FROM A 9000 YEAR OLD SITE IN CHINA

And all of these ingenious instruments had but one purpose: to aid in the creation of human music – an act that, judging by the devotion with which our ancient ancestors applied themselves to it, would seem as important to our survival as the procurement of food and shelter or the making of fire.

Because, to our ancient ancestors, just as it is with us, survival of the body alone was not enough. They wished, as we do, but perhaps even more so, to deeply experience the mystery of life, to touch the fabric of the universe, and to question their place within it. They wished to understand why and how they were different than the animals, who or what gods were, why we became sick and suffered, and where we went after death. And, just as now, they wanted to preserve what they found, to discover in that knowledge a true sense of place, a spiritual center in their hearts to which they might always return, and in which they could foster a living body of knowledge to pass on to future generations.

And so when they created music, they did so not, as is so often the case today, only for entertainment or commerce, but rather to both feed from and nourish the growth of their spiritual center. For in music they found the ability, in a given moment in time, to fully embody that spiritual center and to pass it's essence on to other human beings. The melodies and rhythms they employed, the timbre of their voices and of their instruments, and most of all, their intention, centered their consciousness on this purpose. And all who participated in this music not only listened to and learned it's melodies, rhythms, and techniques, but also absorbed this direct spiritual transmission.

A KORYAK SHAMAN

In this way music took on a sacred, transcendent purpose - to awaken the consciousness of any given individual and integrate it with the timeless continuum of life, suffusing it with the vital awareness both of their ancestry and of nature itself.

Musical culture protected and transmitted this vital awareness, which itself became a living thing, an ancient tree which, though branching onto many cultures and civilizations, had deep roots which predated them all. And human beings, like leaves on this tree, added to its vitality in the course of their short lives, themselves fading away as the tree itself lived on.

To use another metaphor, musical culture was, and is, part of the life's blood of the human spirit.

And yet, like the blood of our bodies, it too has a long history of being shed in violence. Musical culture, like all kinds of culture, like people, can be forgotten, abandoned, assimilated, abused, or eradicated over night. Whole branches of that great living tree which extend to our shared origins have been and are being lopped off without thought for the gaping wounds they leave.

And it was due to the infliction of one such horrific wound that the instrument which we know as the banjo came into being.

A NEW BRANCH

A DEPICTION OF AFRICANS BEING KIDNAPPED

Simply said, the banjo came into existence as a direct result of the kidnapping and enslavement of peoples from the diverse cultures of the African continent during the times of slavery in the Americas.

Enslaved people were taken away from everything and everyone they loved. All traces of culture, from clothing to art, and even language, were denied to them. Their lives were assigned monetary value based on their ability to perform back breaking work for someone else's benefit. All tangible connections to their ancestors, their homeland, were abruptly severed forever at peril of their lives. And the children to whom they would pass on what remained were treated as someone else's property.

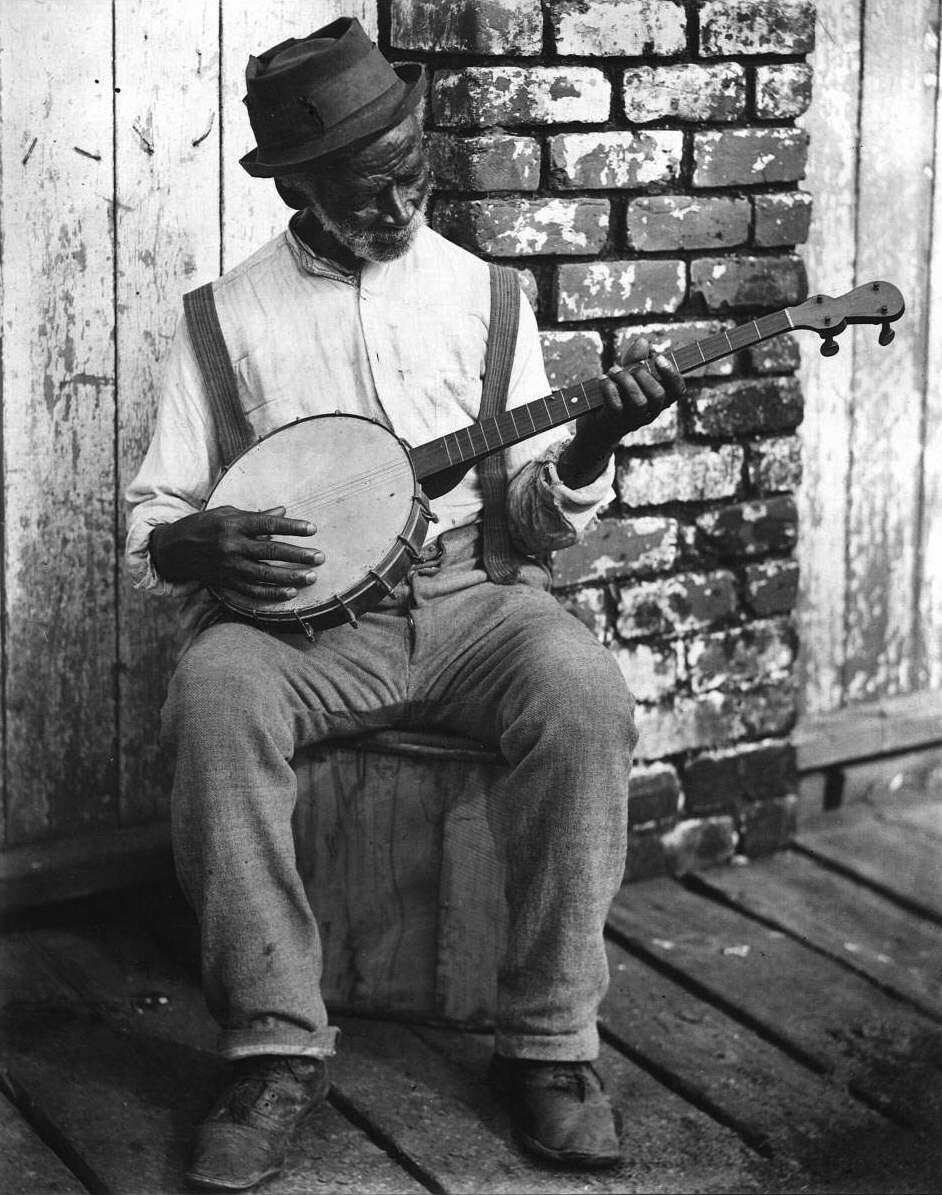

But nothing can take from a person the intangible knowledge which lives in their soul – that essential spiritual center which has been passed down from the beginnings of humanity, transmitted in part by music. So, with only their memories in their hearts and the raw materials around them in the plantations, the enslaved managed to create the ancestor of the modern banjo – an instrument that, like the music it played and the people who played it, was, though descended from Africa, no longer a citizen of any one culture found on that continent.

It was a new sound, a new vibration, one that met the needs of peoples who had no choice but to face each day, come what may, knowing that that they could never return home; people who seemed to have no future at all but for the worst kinds of sufferings and hardship.

REPRODUCTION OF THE OLDEST EXTANT BANJO "BANZA" FROM HAITI, BY 'BANJO PETE' ROSS

The banjo itself, patterned after African instruments such as the akonting, was constituted of an animal skin tacked to a calabash, gourd or other resonator through which a wooden neck was affixed, strung with twine across a carved wood bridge and tuned with wood pegs. It was an instrument of basic design, built with commonplace items.

But in a situation of extreme limitation, even the simplest of items, taken for granted in times of plenty, can be transformed into an object of great function and beauty. Just so with the first banjos, which in addition to producing a powerful, deep, and haunting sound (as we know by the sound of modern reproductions) were also themselves works of art - curvaceous, tattooed, and crafted by skilled hands.

We will never know exactly what the music played on those early banjos sounded like, because recording technology came on the scene centuries too late. But what a sound it must have been – intense enough to interrupt even the most profound sufferings and anxieties, driving enough to replace the drum wherever it was outlawed, hypnotic enough to induce religious ecstasies, fundamental and universal enough to absorb any melody or rhythm it met in the Atlantic world - from the African to the indigenous to the European.

This sound carried with it the living presence of all who contributed to it, even after their deaths. In a world in which the worst of humanity ran rampant, the enslaved managed to foster the essence of life, brought now into such stark relief by looming oblivion, into a new musical incarnation, one which became a powerful source of solace and strength, of transcendence and release.

THE OLD PLANTATION (SLAVES DANCING ON A SOUTH CAROLINA PLANTATION), CA. 1785-1795.—JOHN ROSE

In fact, after their incessant labor, many enslaved people would run miles, at peril of terrible punishment from their masters, to secretly participate in the music and dance which brought them this release. They treated these secret gatherings as worth risking life and limb to experience - as essential to their survival. Contrary to the theory that music is a by-product of wealth and leisure, in the worst conditions these people managed to create the heartbeat of a music which would change the world.

This was a new branch of the ancient tree of musical culture, and it would grow and spread over the years, gradually shaping the soundscape of America. And the banjo itself would undergo many changes, challenges, and change hands many times before it arrived at the present day.

GROWING PAINS

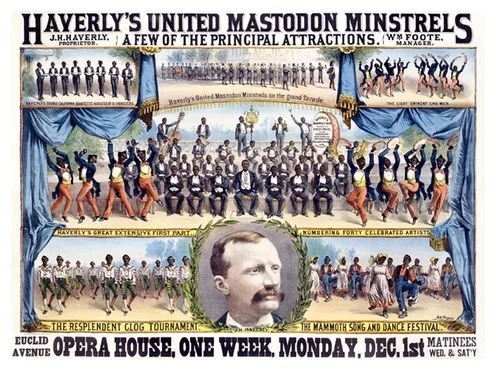

Of the challenges which faced the spirit of the banjo, front and center was the racist form of musical theater known as minstrelsy. Emerging in the early 19th century and lasting a century a longer, the minstrel show was white America's way of indulging it's growing fascination and love affair with the music of the enslaved and their descendants, while simultaneously denigrating and trivializing the enslaved to a degree which enabled the continued denial of their equal humanity.

So, while minstrel shows sparked a kind of banjo mania all over America which led to the mass manufacture of instruments – as well as the publication of printed music and instructional materials – all of this was at the cost of an ever-increasing gulf in the American consciousness between the banjo and the truth of its origins - its spirit.

Indeed, by late in the 19th century, as some instrument designs and playing styles grew apart from the minstrel show, a near to complete denial or ignorance of the African american origins of the banjo became possible for white America. And what's more, though some African Americans continued their banjo playing tradition, many began to prefer other instruments, such as the guitar, to carry their music into the future.

CELEBRATED APPALACHAIN CLAWHAMMER BANJO PLAYER CLARENCE ASHLEY

However, concurrently with all of this, and due in fact to the mass manufacture of instruments and the popularity of the minstrel show, the spirit of the banjo found it's new home in an unlikely place: the rural Appalachian mountains.

The largely Scots-Irish settlers of these mountains were no strangers to harsh circumstances. Poverty, hunger, low-paying and dangerous labor, extreme isolation and the psychological pressures begotten of it were a constant threat to life. And so the mountain people, magnetically attracted to it's sound, adopted the banjo from both the minstrel show and their black neighbors, alongside of whom they developed a new music.

Often playing in a downstroke style which, unbeknownst to them, first came from Africa, the mountain people used the banjo to play songs they remembered from their former homelands, to communicate news, to ease their burden of suffering, to quiet their anxieties, to fuel their dances, and to make utterly unique music as they absorbed the new sounds of the American cultural and natural landscape. Banjos, as they were designed to do by their overlooked creators, brought people solace, strength, transcendence, and release.

But the challenges facing the spirit of the banjo were far from over, as we might well know by the negative stereotypes which have, until recently, overshadowed the fascinating and painful truth of its story and the haunting beauty of it's sound. Yet thanks to the persistence of strong regional traditions, the love and devotion of players, and the determination of historians, its story and spirit survives.

NEW POSSIBILITES

So when you pick up a banjo, even one fresh off the factory floor that has never been played, you are picking up this and countless other stories - some known, some lost, some yet to be discovered. And if you let it, maybe the spirit of the banjo will speak to you. And when it does, it will not merely tell you the tragic story of kidnapping, racism, violence, isolation, fear, and suffering - though all of those are part of it. What it will tell you instead is the story of hope as it sings loudly and proudly in a world which has never succeeded at extinguishing it, and of the many people who have devoted their lives to hearing that spirit and making it heard.

Perhaps, knowing the tremendous sacrifices that people made and were willing to make in order to experience the music of this humble instrument, we could begin to see the banjo not only as a relic, curiosity, or symbol; we could see it as part of our own cultural and spiritual life's blood. Imagine the power of the music we could create if we understood, even half as much as our forebearers did, just how essential that life's blood is to the growth and survival of our own spirits.

For my part, I hope to visit ever more often that crossroads in which my spirit and the spirit of the banjo meet in mutual understanding, ready to make music in harmony together. I know that I cannot force the instrument to speak in a way untrue to itself, but neither can I deny it its most defining characteristic – the ability to adapt to, absorb, and change existing musical styles, in order to create new music which suits the deep personal needs of whoever might pick up the banjo, wherever they may be.

Chris Rippey performs "The Chickadee"