Consciousness and Landscape

Consciousness and landscape

Renowned translator David Hinton on nature, creativity and the ancient Chinese mountain poets.

Hailed as "simply the best translator of Chinese poetry presently working in English", David Hinton is an internationally renowned expert on Asian culture and literature, and a preeminent translator of the Chinese classics. Through his writings he has produced a body of work that explores the weave of consciousness and landscape; an exploration informed throughout by the insights of the ancient Chinese sage-masters. Viewing his translation work as a kind of apprenticeship, Hinton has recently moved on to a style of writing of his own that embodies the deep perspective and experience he has gained in his 30 years of working within the ancient Chinese tradition.

THE ROOTS OF ROOTS

CV: How did you find your way into translating ancient Chinese poetry?

DH: I initially found my way into it through reading modern American poetry. Beginning with Ezra Pound, the modern poetry of the West has been heavily influenced by the ancient Chinese poetic tradition, which has its philosophical roots in Taoism and Ch'an Buddhism, also known as Zen Buddhism in Japan.

TU FU (712-770)

In my readings, within a week or two I happened to come across several sources claiming that Tu Fu, a very well known figure in ancient China, was considered to be the greatest poet in human history. Naturally I tried to find out more about him, reading everything in English I could, yet none of the translations I found gave me the impression that his writing was all that significant.

Then I came upon a book that gave 30 or 40 of his poems in all the stages of translation —from the original Chinese ideograms, to word for word translations, line for line translations, and then prose translations— so you could see the whole poem from beginning to end, as if you were translating it yourself.

From this I realized his poetry was indeed truly remarkable, and that there was so much in his writings that was lost in the translations I'd been reading. I found these were not just poems about traveling, or chrysanthemums blossoming, or longing —they were indeed about all of that— but these experiences were being expressed from a very different place, a different worldview than the context that traditional Western poetry had grown out of.

I noticed this deep interpretive context was lacking in the English translations I came across, and so I decided to begin studying Chinese, and started translating myself. The more I translated, the more focused I became on providing this context in my introductions. It took a book or two for this to really happen, and the more I focused on the framework, the more I felt I could open up what was really going on within the writings.

In order to go deeper into the cosmology of ancient China, I also translated many of the seminal philosophical works such as the Tao Te Ching and the Chuang Tzu. I actually have an I Ching coming out this fall, which is probably the last of this type of work that I’m going to do.

More recently I’ve started writing my own essays about this worldview, my experience with it, and how for being so ancient, it's miraculously still very relevant to those of us living in the world today.

Autumn Begins

Autumn begins unnoticed. Nights slowly lengthen,

and little by little, clear winds turn colder and colder,

summers blaze giving way. My thatch hut grows still.

At the bottom stair, in bunchgrass, lit dew shimmers.

— The Mountiain Poems of Meng Hao-jan

Language, Perception and Experience

You mentioned that ancient Chinese poetry comes out of a very different worldview than the Western poetic tradition. What makes it so different?

Well, ancient Chinese is a pictographic language, which means that it has a very direct connection to the world. The characters share their source with the things they represent, like a tree. This creates a sense of continuity between the character and the source.

In contrast, the alphabetical language of the West is not representational, and because of this it's more abstracted from direct experience. It has the effect of creating a sense of division between the viewer and what is viewed. This reinforces an ‘I’ reference point, a completely separate, self-contained identity that feels apart from and looks out onto the world.

But in the poetry of the ancient Chinese, you rarely see them say ‘I’. Their poems don't have subjects, but rather a kind of empty grammatical space that you fill in as you read- a kind of absent presence. And this is the really crucial point, that this ‘I’ self-center is not so present in the ancient Chinese language.

not aware beginning autumn night gradually long

[I] didn't notice autumn beginning

In the physical world mountain ranges rise and fall, as do the grasses and the flowers in the fields. You can see it in the process of the seasons, where spring is the burgeoning forth from emptiness, summer is the fullness of life, autumn is the dying back, and winter is the return to this pregnant emptiness.

So through meditation they could see that out of the same emptiness thoughts come into being, last a while, and then dissolve back into emptiness. And if they watched long enough eventually their thoughts would stop - and then they would be inhabiting just that empty space where things come from, sitting right at the generative heart of the cosmos.

This way of experiencing the world is quite different from what we normally perceive in the West, where we think of ourselves as these sort of independent spirits, and that our minds are these intellectual centers that operate in a separate realm, a kind of spirit realm, as opposed to the material realm of the earth.

And that's really what spirituality was for them, which again is indeed very different than the West, where it's often about faith and prayer and all of these sort of extraneous things, rather than being about self cultivation, about cultivating a sense of belonging to the earth.

So that worldview is present within all of the poems of the ancient Chinese, and I think it’s what makes them feel so different from traditional Western poetry.

How has working with this type of language and perception influenced your writing style and approach?

Well, translating the poems has made me inhabit this understanding on a really deep level, which has changed I think how my mind is structured and works. I've learned that if you pay attention to what happens when you’re actually seeing the world —when you’re really seeing something— you realize that you’re not actually there at the moment of seeing, only afterwards. In the moment of seeing you’re absent, and in fact if you’re preoccupied with thoughts and worries, your attention is there and not in seeing.

So for the ancient Chinese, this idea of seeing the world clearly and immediately was both an art form and a real spiritual practice. And when I am rendering this perspective into English, it makes me think ‘so how do I make this kind of structure of consciousness work in the context of our world?’.

In my recent book Hunger Mountain, I explore this process through my walks up the mountain close to my home, contemplating the physical and mental contours of nature and consciousness. In the book I give each chapter a Chinese title, which usually gets traced back to its pictographic sources, and then I weave this theme into a narrative that reflects my own experiences living with the ancient Chinese poets and their cosmology.

And that's what I’m doing now more and more in the essays, is trying to flesh that out. As I’ve moved back and forth across that frontier for the last 30 years or so I've become very familiar with the process, and am now working out a way to communicate this experience directly through my own writing.

A Way you can call Way isn’t the perennial Way.

A name you can use to name isn’t the perennial name:

the named is mother to the ten thousand things,

but the unnamed is origin to all heaven and earth.

In perennial Absence you see mystery,

and in perennial Presence you see appearance.

Though the two are one and the same,

once they arise, they differ in name.

One and the same they’re called dark-enigma,

dark-enigma deep within dark-enigma,

gateway of all mystery.

—Tao Te Ching

PARALLEL WORLDS

What was everyday life like in the time and place of the ancient Chinese poets, and how does this compare to living in our world today?

What's amazing is that their lives were actually very similar to ours. All the poets, the intellectuals, the artists and Ch'an monks were part of the intellectual class, and people in this class assumed that their place in the world was working in the government to help the emperor take care of the people. That was the ideal form of course —how well that was carried out is another matter— but they were basically bureaucrats working in offices, just like most of us are in one way or another.

So their lives were very textual, very erudite, and within that world they felt I think like many of us feel- when you’re in an office doing this text based work there’s a certain amount of alienation from immediate experience, from something that's more deeply satisfying than just your mental processes.

So every chance they had they would go out into nature, into the mountains. They would go on vacations, or they would sometimes quit their jobs because they just couldn’t put up with that disjunction anymore. Sometimes they were also exiled because they got on the wrong side of power, which meant they could go live a simpler life in the mountains, which to them was in a way a kind of blessing.

So all of these people had two sides- one was the Confucian, which was the political/social side, and the other was the Taoist, which was the spiritual/artistic side.

When they were in the mountains, they were focused on that spiritual side, and that’s where their art came from. That’s where they felt they could truly be. Spiritual practice for them meant to cultivate a sense of belonging to the cosmos as a kind of generative organism, where they could be a part of the changing of the seasons, of night and day, life and death, without setting themselves aside from or resisting the natural processes of life.

In some ways that reminds me of the many people today who are moving away from cities and embracing things like the farm to table movement, and other environmentally conscious ways of living. However, it sounds like the worldview you're describing could add another, perhaps deeper dimesion to the values currently developing within our culture.

Yes, and thats really what I’m trying to do. In fact because it's a very empirical perspective —rather than the type of cosmology that the Judeo-Christian tradition has passed down, which in many ways has become outdated— in comparison I think it’s very compatible and even sort of familiar to us living in the modern world.

I’ve actually just been thinking about this again for the book I’m writing- that ancient China actually went through a similar process very early on in their history.

Around 2000 BC, they had a religion that supported a theocracy- the emperor claimed to be a sort of descendent from a monotheistic god, and that was how he was able to keep authority over the country.

Eventually that monotheism broke down into the worldview I've been describing. So in a sense, ancient China about 3,000 years ago made the transition we are making today from this kind of monotheistic worldview, where everyone experiences themselves as a spirit —a kind of extension of the spirit world— to a more earth based type of spirituality.

EAST MEETS WEST

You mentioned how ancient Chinese art forms had a very strong influence on modern American poetry. Can you say more about this?

Well in general that influence began about 100 years ago with Ezra Pound, when he discovered Chinese ideograms. He was trying to re-fashion Western poetry away from abstraction, rhetoric, and linguistic embellishment —which is a kind of crystallization of that Western spirit-self I mentioned— into something more concrete and immediate. So he invented imagism, a poetic style that focuses on images as expressive in and of themselves, rather than being simply embellishments, or somehow tied to human self involved thinking and self dramatization. And he really found a model for that in the pictographic language of the ancient Chinese, in the clarity of the language itself, and the linguistic-grammatical structures.

And then because ancient Chinese is so involved with landscape and environment, it also became influential after World War II, with Rexroth and Snyder, who were translating and writing a type of environmental poetry.

And beyond that at a deep level, this idea of accepting your immediate experience —sort of celebrating it no matter whatever it is, rather than thinking it has to be picture postcard perfect before we can engage with it— that acceptance, that commitment to everyday experience has really become the framework within which just about all contemporary poetry works in America. It’s suffused poetic practice in those general ways, and also in more technical ways that are probably too specific to talk about here.

So the overall worldview has been influenced by the Taoist and Ch'an Buddhist thinking, and Tibetan Buddhism too. In fact, Buddhism has become practically the official religion among innovative artists of all kinds, and if you ask artists about their views, they often reference something that leads to Taoism, or some kind of Buddhism. So the influence is indeed all over the place.

You mentioned you are working on a new translation of the I-Ching, and this will most likely be your last translation of a seminal work. Are you taking any particular approach to this text?

Well, although it's mainly known as a divination text, and that’s how people always look at it and really think about it, in ancient China the intellectuals saw it primarily as a type of literary philosophical text. All of the philosophical texts in ancient China were very literary, with lot’s of story telling, not analytical systematizing like in the West. So I see the I Ching as really the first glimmer of that whole Taoist-Buddhist worldview.

MEDIEVAL I CHING MANUSCRIPT

Most translations are often made up of layers of commentary, and so I’m trying to go back to the original text of the I-Ching, eliminating the later commentaries. The editions that people know in the West, especially the Wilhelm edition that everyone uses (which is around 800 pages long) consist of mostly later commentary that is not part of the original text.

So I’m going back to the earliest levels, and my translation is only going to be about two pages per hexagram, so around 128 pages long. I’m trying to let it stay more mysterious and poetic, and like I do with the poetry I'm really trying to draw out that philosophical and cosmological framework that's embedded within it.

And as you said, since that’s the main style of communication that all of the seminal texts are written in, I suppose it would only make sense to apply that to the I-Ching.

Yes, and I don't think that those things have been really drawn out that well in the West. And that’s what I’m trying to do- I’m trying to present this stuff in its native philosophical context, its native form, rather than through a lens of not-quite-getting-it, or a lens that simply filters it through Western ideas. Much of the framework is lost because it doesn’t sort well with Western categories and concepts, so I’m trying hard to just bring out that Chinese framework, and also to show how in fact familiar and contemporary the whole thing is.

GESTURES OF THE COSMOS

How did this philosophical context relate to the other arts in ancient China? Was it similar to poetry?

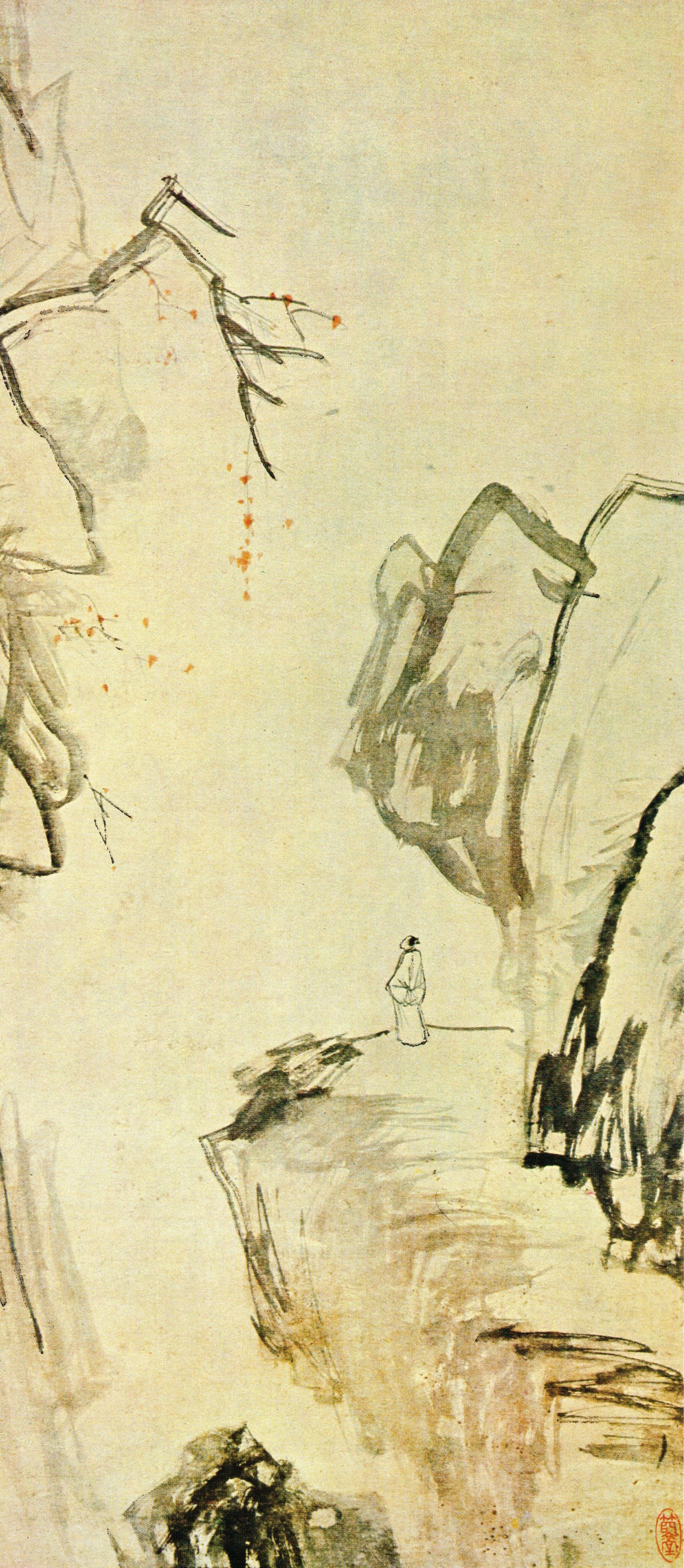

All the arts —calligraphy, poetry, painting, and music too— were considered forms of spiritual practice, ways of experiencing that cosmology at a deep, immediate level in everyday life. To look at a landscape painting was an act of meditation. In fact, the Chinese approach to painting is very different than traditional Western painting. In the West paintings are often made of oil which is very thick and covers the whole painting, whereas the Chinese use a thin water-based painting style that leaves a lot of empty space. It represents that kind of pregnant emptiness I was describing that’s also in the poetry.

And so you see this emptiness as space, which is in consciousness and in all of reality, and then there’s the landscape emerging out of it. And in ancient China people could apparently lose themselves for hours looking at one of these paintings, because it was a kind of spiritual practice, a meditation. So there was this broader context for meditation that included all of the arts.

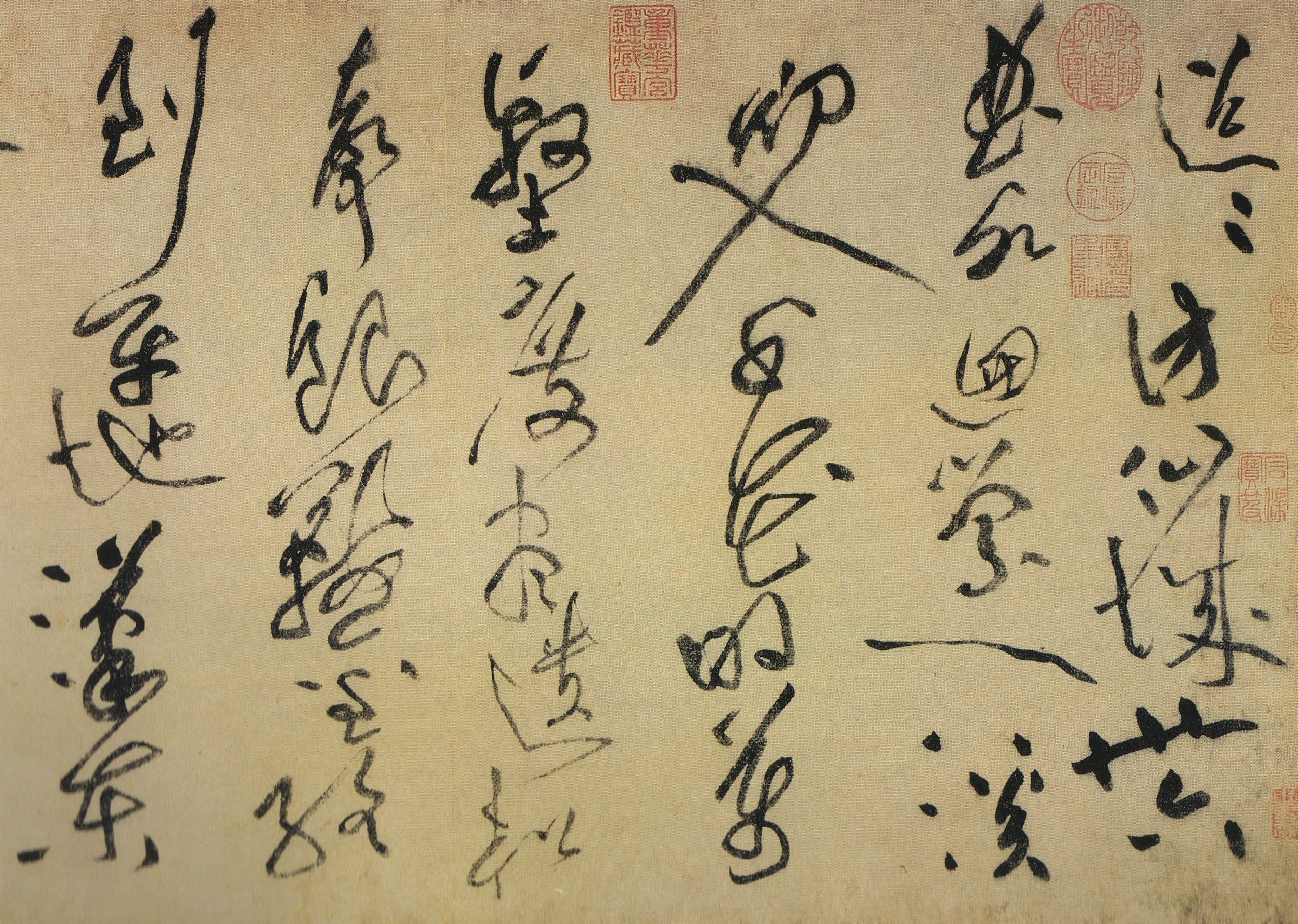

I actually have another book of essays coming out that goes into this, and shows how that sense of consciousness woven into the cosmos is present in all the different Chinese art forms. I talk about poetry and painting, and then show examples of poems and paintings so people can have an immediate direct experience of them. And also calligraphy, which is still pretty mysterious to us, because it's a Chinese art form that has absolutely no corollary in the West. People want to look at it as fancy handwriting, but that’s not what it is at all. Actually the closest corollary in the West is Abstract Expressionist painting.

So I talk about that and explain how calligraphy really works, and then show some great examples of it, and let people experience that inner world of calligraphy, painting and poetry.

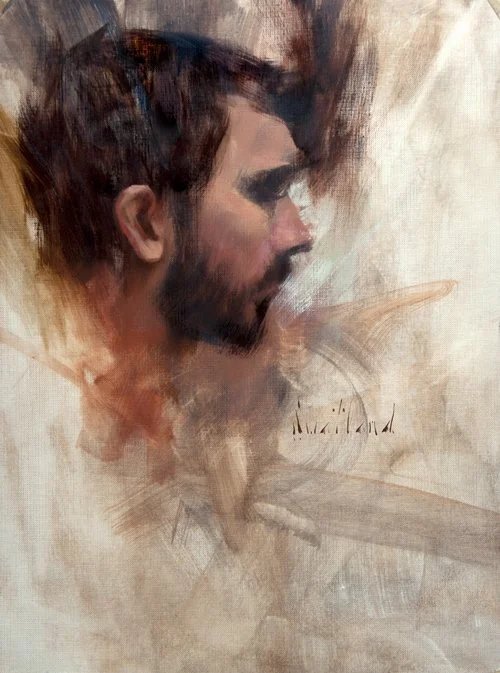

The way you're describing calligraphy reminds me of watching artist Katie Swatland paint. In the beginning of the process she's creating these abstract forms, and then the forms slowly take shape into something that becomes more of a realist-type painting. This type of painting process appears much more dynamic than the style often associated with traditional Realism.

Yes, because that kind of gestural approach is making paintings that are revealing the generative process of the cosmos, the energy of the cosmos. It’s not trying to simply make a picture of something, it’s trying to enact that kind of selfless creative energy of nature, which is what’s going on in Chinese calligraphy and painting. So there’s lots of connections to painting like that.

That also parallels my experience with music, where it can be seen to be made up these different vibrational properties —sounds that are in opposition and harmony, forces that yield and contract and expand— and from this point of view an emotion becomes the same as the calmness of a lake, or lightning, or a rainstorm- there's no separation at that point between inner and outer experiences.

That’s fantastic. In Chinese Chin music, the old Chin tunes often have names like 'the swans come to the lake', or 'rainstorm in the mountains', or something like that, and they felt like that’s really what was happening in the music. I think it’s very much like the kind of thing you’re describing.

‘Flowing Water .’—Guqin traditional song

I think so too. And it also shows that even without the metaphysical worldviews of the past, there can be an approach to a way of living that’s deeply spiritual and also empirical, simply rooted in our direct experience of the world.

Very exciting. It’s nice to hear that you're working out the same thing but in a different direction. It’s been a big slow cultural process that's been going on in the West for over half a century really, and a lot of it has suffused the culture in subtle ways that people don’t often realize.

Just the other day I was driving home from Boston with my daughter and the song Stairway To Heaven by Led Zeppelin came on the radio. I hadn’t heard it in like 30 years, and right in the middle of it, the crux line is something like ‘the stairway to heaven is in the sound of the wind and the trees’. And I thought, in the middle of this big rock and roll extravaganza, that's totally Ch'an Buddhism! And so that’s how it’s suffused the culture- you find it all over the place in these subtle ways.

Autumn Begins

We live in a sea of stories, like this story I am telling here about landscape and consciousness, and each is an assertion of a center of identity, but . . . when we bow, we offer the center to something beyond, to something beyond the stories we tell ourselves about the world, the poems and philosophies and mythologies that shape the center, and this poem ends with a bow. It ends with a mind so empty it can shimmer with dew, and this is a remarkable place, an emptiness where we come face-to-face with the most elemental of miracles: Presence in all its silent radiance.

—Hunger Mountain