Revival and Evolution

Revival and Evolution

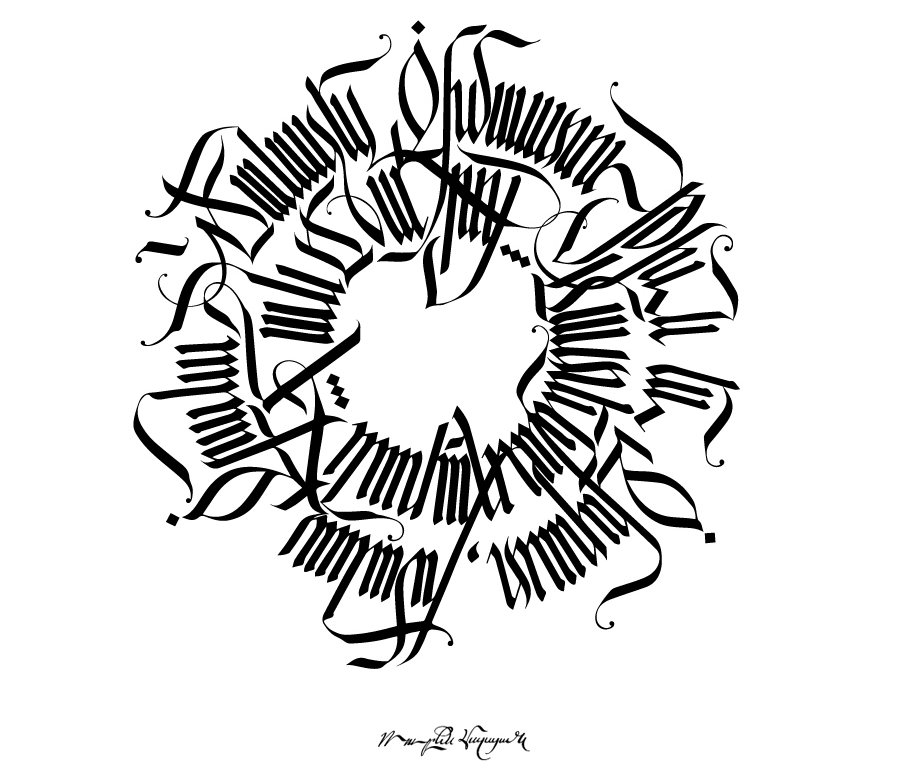

An Armenian artist’s calligraphy embodies the struggle to sustain and advance the soul of his culture.

Award-winning art director, calligrapher and visual artist Ruben Malayan's career in graphic design spans over twenty years — crossing over into the fields of visual identity design, typography and calligraphy. For over a decade he has been working on research about the art of specialized scripts, and has developed a portfolio of unique Armenian calligraphy. Ruben is also notable for his work in social activism, as a founder of the 'Armenian Genocide in Contemporary Graphic & Art Posters' project, and for his protest art contributions to the 2018 Armenian Velvet Revolution.

watch ‘the art of Armenian calligraphy’

What inspired you to dive so deeply into the traditional calligraphy of Armenia?

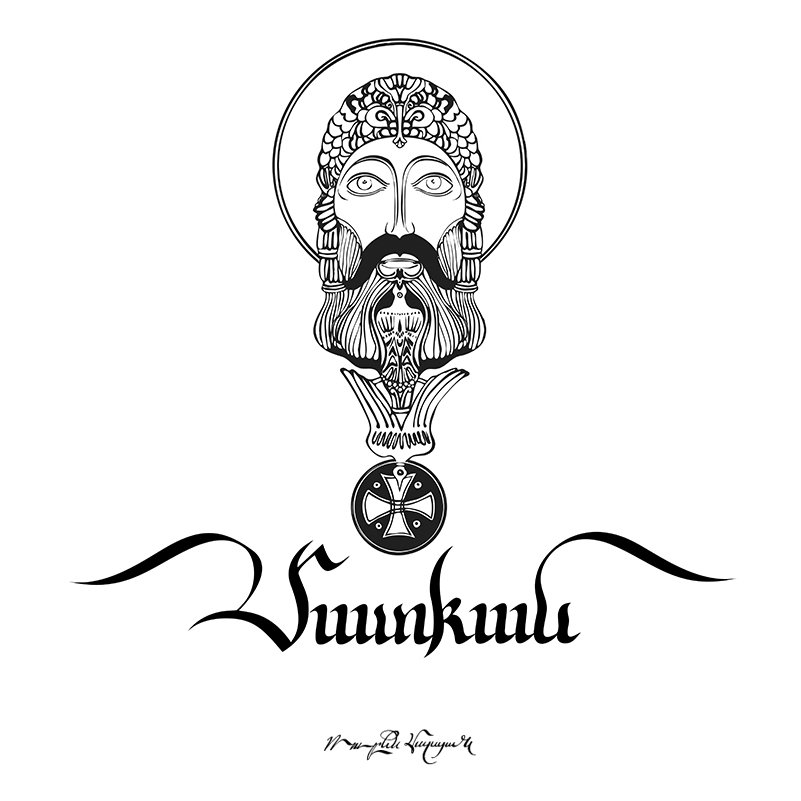

I was trained as a visual artist and the art of writing has always fascinated me. Our culture is very rich with letterforms, and the Armenian alphabet is one of the pillars of our identity. Not every nation has an alphabet that is used exclusively for its language, and I guess we are lucky in that way.

My initial curiosity about calligraphy was sparked by examples I saw when I was growing up; interestingly, they were mostly from Eastern cultures, specifically Japan. My father owned a book with reproductions of Hokusai paintings, and I was captivated by the lettering culture I discovered in that volume. I was a kid then, and it impressed me deeply.

Traditional Japanese Lettering

What do you feel the value is of learning to write in a calligraphic style today?

I think we have trouble keeping up with technology. It evolves so quickly that many artists feel a constant need to go back to analogue forms—to materiality. I think that’s quite natural, because the more we move toward the virtual, the more we will feel the need for something tangible—something which does not depend on devices or battery power. Writing on paper is fundamentally different from typing. The process of struggling with the material produces friction, which in turn teaches us commitment and discipline. I don't really like the ease of undoing one's mistakes when work is done digitally. Even though it has many advantages, I still prefer paper.

We must acknowledge that there is an immense difference between writing and calligraphy, however beautiful the former may be. As Claude Mediavilla put's it, it’s "the difference between reproduction and creation, between repetition and invention". Calligraphy is art, and by virtue of that fact it pursues different goals from writing. I suppose in that sense it echoes other forms of visual artistic activity—its most significant value is a creation of aesthetically pleasing, balanced forms.

However, what makes calligraphy stand apart from, for example, abstract painting, is the aspect of legibility and essentially the intended message. I often see very impressive work by talented artists, but I fail to see a message—it has none. It says nothing beyond the fact that it is a beautiful sequence of strokes. I find it difficult to call that calligraphy. Excessive repetition of deconstructed letterforms turns it into ornamentation and that tires me quickly. I think the message is very important, especially today.

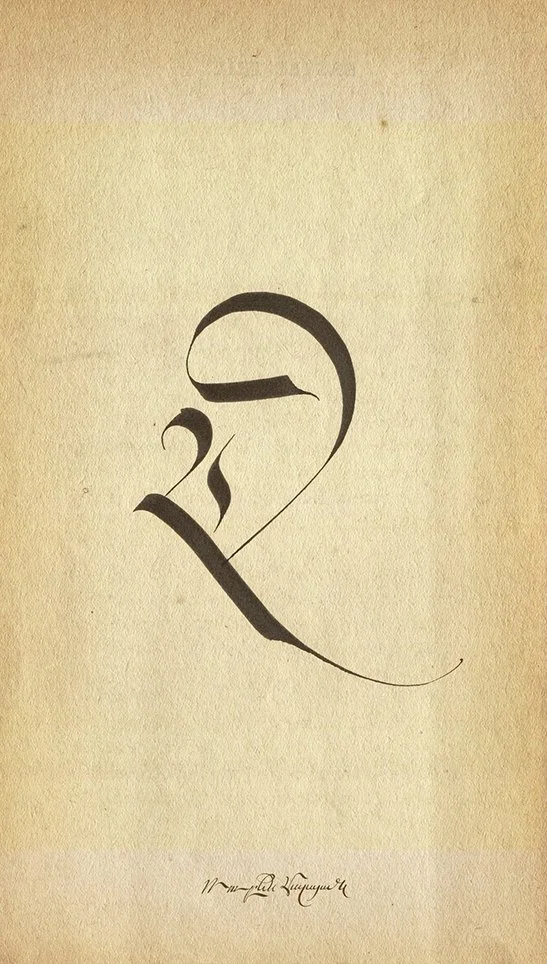

RUBEN WRITING THE ARMENIAN WORD FOR ‘HOME’

You’ve been attributed with helping to revive the knowledge and practice of traditional Armenian calligraphy within your culture—what caused this tradition to fall into such obscurity, and what has the process been like to bring it back into being?

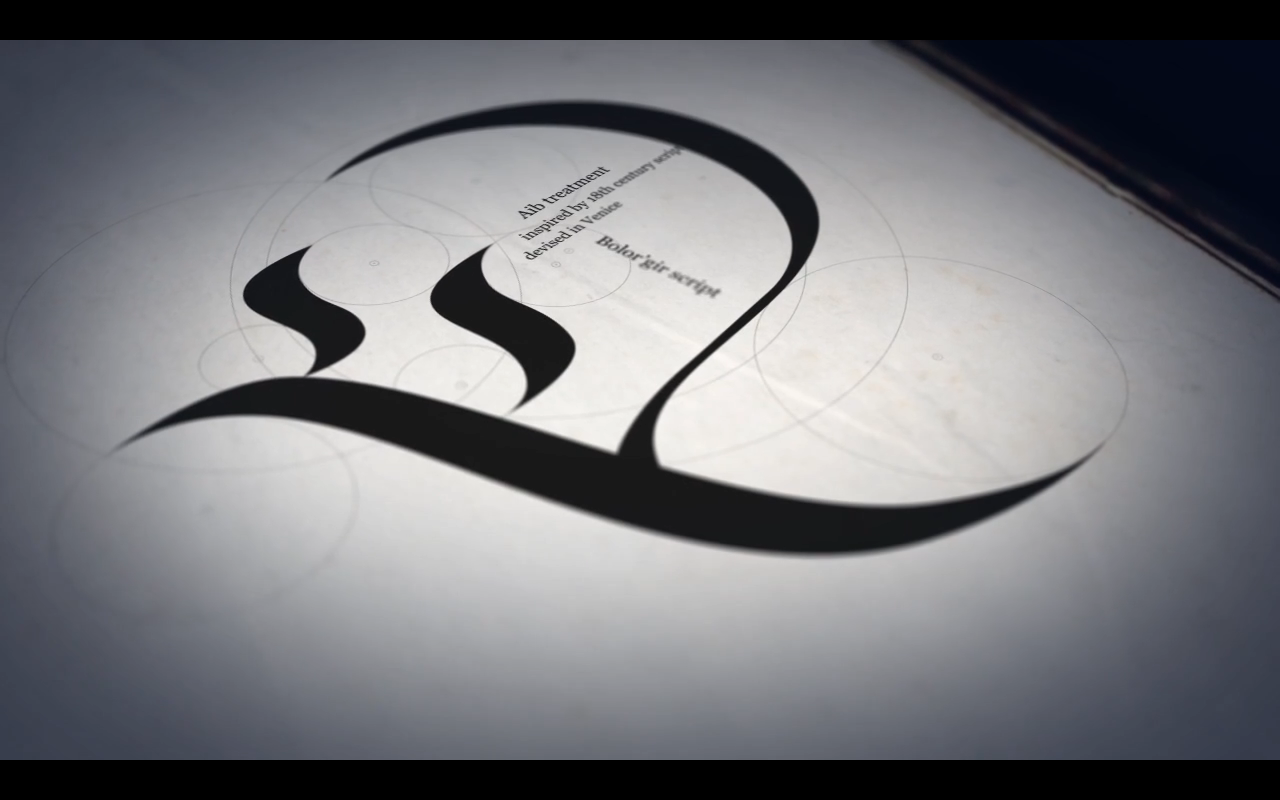

When we use the term 'traditional', we may mean different things. Traditional calligraphy refers to the formal way of writing. We have scripts which were used for many centuries and without much alteration. I am more interested in trying to come up with a way to fuse those with new aesthetics that are perhaps more modern, more relevant today.

Essentially, the traditions of calligraphy were always connected to religious practice. Sacred books were, of course, written by hand, and the style of writing conformed to the period of their creation. When the world took a turn toward industrialization, the religious factor began to lose its urgency; printing replaced handwriting and calligraphy was not practiced as much anymore. It became the domain of artists and designers, not scribes.

Designers, especially typographers, understood the importance of experiment on paper. We must remember that without it, new typefaces would never be created. Some of the great typographers of the past century, such as Rudolf Koch, Hermann Zapf and Jan Tschichold, were famous for their calligraphy. They practiced it incessantly. That’s why their typefaces are so rich and balanced and still very much in use today, as they were when they were created. So if we want our letters to be relevant—to have a long life—we must figure them out on paper first, before adapting them into digital format. So as with typography, calligraphy must follow the same principle—it must be expressive of content.

If the value of culture declines in a society, this fact is first reflected in the arts. Armenia has had a very turbulent history, and since the fall of the Soviet Union thirty years ago, the country has been fighting for survival. We don't have the good fortune of friendly neighbors, and throughout our history, we have always had to resist cultural assimilation. Our spoken and written language was that last line of defense, so to speak. That’s why it was, and still is, very important not only to preserve it, but also to develop and enrich it further. And it is a constant struggle—a struggle against visual illiteracy and a general disregard for aesthetics.

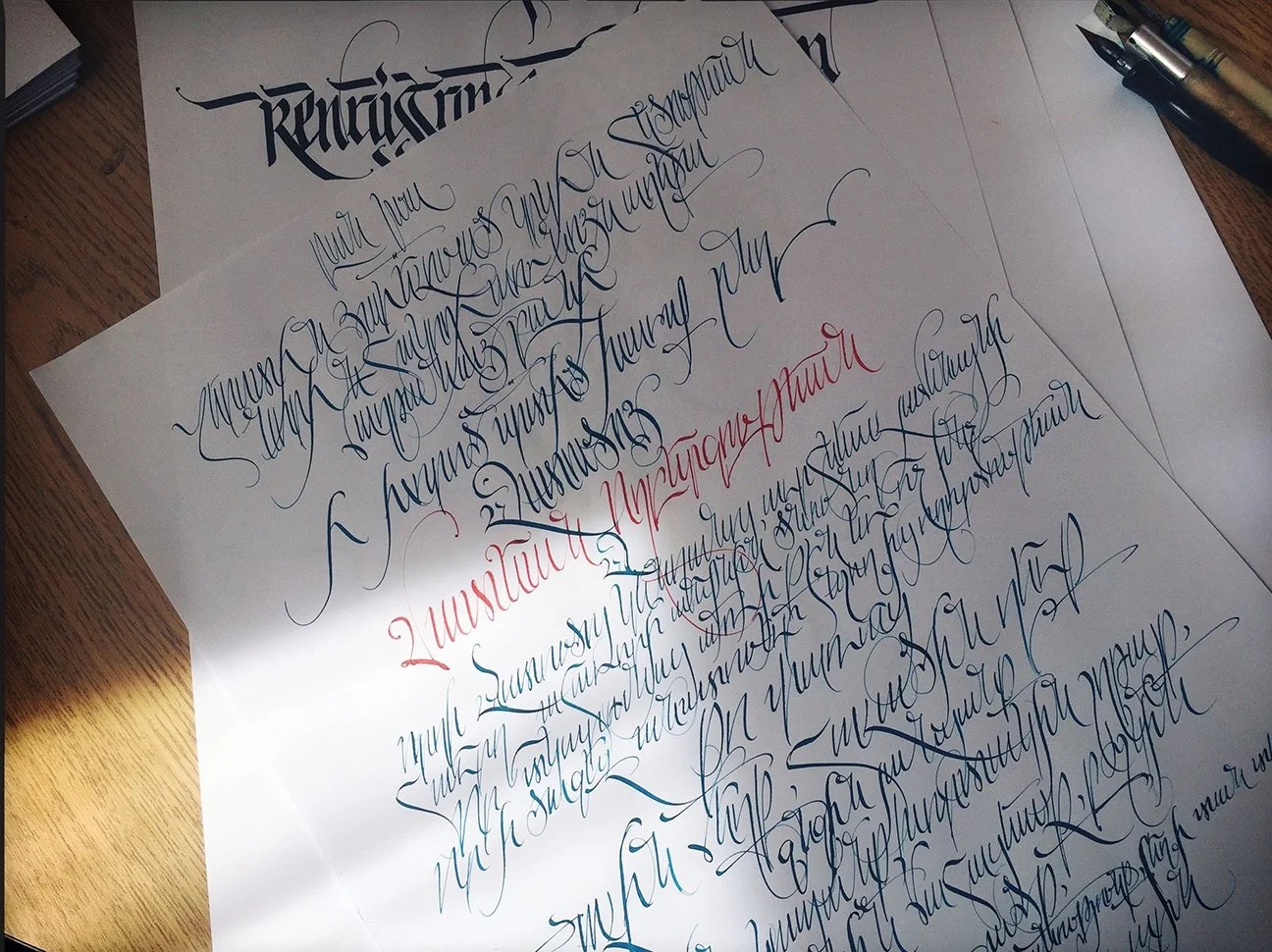

‘TO KNOW WISDOM AND INSTRUCTION; TO PERCEIVE THE WORDS OF UNDERSTANDING.’

— BOOK OF PROVERBS, 1:2.

Recently you utilized your skills as a visual artist and calligrapher to contribute to the nonviolent political protests in Armenia. Can you speak a little about this experience?

The political protests you refer to lasted for four weeks and culminated in a non-violent revolution (learn more here). People have had enough of corrupt politicians, of poverty and emigration. The past thirty years have seen Armenia lose more than half of its population to emigration. Change was necessary.

I must say that what happened in Armenia was unprecedented, especially when we consider the methods people used to oppose the government. Not a single shot was fired and no violence was used by the protestors. The sheer number of people on the streets is what forced those in power to surrender.

'All will be well'

I was part of that movement as a citizen and also felt responsible as an artist. Art can be a weapon, especially when it takes the form of a poster. I wanted to express visually what we all felt—what needed to be said, needed also to be put down in writing. So I started drawing posters and giving them out to the people on the streets. I understood the importance of having the message written, not just in Armenian but also in English, as we were watched by the world through constant live streaming.

The energy charge was immense and I was happy to be able to transmit it into materiality. The messages were concise and articulate—poster medium requires that. But it was a test field for me as well, as I moved to work on a large scale. Calligraphy nibs were replaced by pump markers. Paper was not practical, so I worked on foam PVC boards, which were light and durable, perfectly suitable for the task.

To my surprise, toward the end, I moved closer to abstraction, which was a real revelation for me. I am a figurative painter, you see; abstract work was always somewhat beyond the reach. One of those abstractions was drawn in less than a minute and I was driven entirely by intuition. When I was done with it, I was shocked to see the result—I had drawn a two-headed monster of the “Counter-revolution.”

When it was over, I opened an exhibition of the posters, some of which remained in my possession, and many people came to see them. It was very gratifying. I think their own energy was transmitted back to them through the art work.

‘COUNTER-REVOLUTION’

What do you hope to ultimately contribute through your art?

Art is a mirror. It always was and will remain so. Artists need to be conscious of the social responsibility of their work. We need to be at the vanguard of positive change in society. We need to be the honest voice that always speaks the truth. It may sound idealistic and somewhat naive, but I do believe that through the beauty of art, humanity will eventually evolve beyond ego, beyond personal interests. And I hope I can contribute to that evolution.

— For more information about the work of Ruben Malayan, please visit —

Armenian Calligraphy — Instagram — Armenian Revolution Posters