A Classical Revolutionary

A Classical Revolutionary

George Saumarez Smith discusses the foundations of his art, and makes his case for its revival in the field today.

George Saumarez Smith is one of the leading classical architects of his generation. A Director of ADAM Architecture, one of the most prominent firms practicing traditional architecture and contextual urbanism in Europe, his work has included new buildings, extensions and repairs to historic properties, as well as consultancies for urban master-planning. A recipient of numerous awards, in 2011 he was the first classical architect to be shortlisted for the Young Architect of the Year award. He has authored A Treatise on Modern Architecture and teaches, lectures and writes regularly on a wide range of subjects relating to traditional architecture.

GEORGE'S TEDx TALK WITH FRANCIS TERRY ON CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE

Historical Roots

Can you speak a little about what classical architecture is, and how you found your way into the profession?

Classical architecture wasn’t defined as such until the middle of the 20th century, when most architects began to practice what came to be called modernism. At that time they needed to give the more traditional approach to architecture a different name, so that people recognized it as something distinct.

And so what came to be known as classical architecture began in antiquity, where the architects of ancient Greece and Rome developed a set of rules for building based around different kinds of column, called The Five Orders. These rules formed the basis of architecture in western culture for the next 2,000 years.

Sometimes this view is disputed —for example some might say that the Gothic architecture of the middle ages is totally different from classical architecture— yet I would say if one looks at the history of classical architecture, it's all a series of revivals. So Gothic architecture is really a kind of memory of classical antiquity, and then in the Renaissance it gets revived in a different way through measurements and the humanist tradition. And then it’s revived again in the Neoclassical period, the Beaux-Arts period, and on throughout history. So the history of classicism is actually the history of revivals.

And how did I find my way into it? My exposure began at a young age. My grandfather was an architect named Raymond Erith, who practiced as a classical architect at a time when very few other people did, during the 1930’s through the 1960’s. So the knowledge was always present within my childhood that classical architecture could still be done.

My grandfather also took on another very well known classical architect, Quinlan Terry, as his apprentice. Eventually they formed a partnership together, and after my grandfather passed he carried it on. I then worked for Quinlan when I was a student, and also studied in Edinburgh, which is a city very rich in classical buildings. So growing up it was always very reassuring that I had a complete link with the tradition.

CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE IN EDINBURGH

DRAWING AND SELF RELIANCE

What was your experience like pursuing a classical architectural education in school?

Because the teachers who had known and practiced classical architecture had long since retired, it was very difficult to get any proper teaching about it. The people I was taught by were generations of architects from the 60’s and 70’s, and by that point classical knowledge had been completely excluded from schools of architecture.

Schools always stay slightly ahead of what architects are doing in the field, and so when I started saying I was interested in designing classical buildings and talking about the orders and so on, they treated me almost as if I was a sort of child who hadn’t yet grown up. They gave the impression that there was something slightly wrong with me, and I needed to be re-educated away from that into the things that they were interested in.

Yet being in a city where you see classical detail on every other building, you begin to think to yourself, ‘why was all of this so rejected, and why doesn’t anybody know about it anymore?’. And so a lot of my teaching I discovered for myself, and in a way the hostility towards doing classical architecture actually had the effect of fueling the fire in my belly that little bit more.

I‘ve also seen footage of you creating architectural drawings- is this something you taught yourself as well?

I’ve always loved drawing, and I suppose this type of drawing is something that you don’t see often today. When I was in university I started going around with a tape measure, scale rule and sketchbook, and just recorded things that looked nice.

I found that if you do this enough, you begin to train your eye to recognize the things that look good, and then when you go to put them down on paper you sort of instinctively know what good proportions are. So I found that sketching a lot out in the real world, drawing what buildings and trees and people actually look like, can be very helpful.

And drawing live is quite fun, because in a way people expect classical architects to be rather old fashioned and slightly fogeyish, and so it’s always quite nice to come out and do something they’re not really expecting.

I do suppose that since my generation has taken to working with computers, a lot of the traditional drawing skills are starting to be lost. So as with classical architecture, I'm trying to hang on to things that many other people have discarded.

A Sense of Order, A Sense of Place

You mention in one of your essays that the Five Orders can be used on different levels of scale to build anything from ‘a table to a temple’. Can you say more about the orders, and the qualities they represent?

When you design a building, you have a sense of which of these five different modes you will be working in. It may have to do with the kind of decorum, or it may be related to the client or the site.

To categorize them simply:

The Tuscan is the most rustic, and tends to be more associated with very tough buildings, like prisons, or ones that have a sort of defensive purpose.

The Doric is very male, it's traditionally associated with strength, and so if you are designing a military building or perhaps a mausoleum you would immediately think of the Doric.

The Ionic is more feminine and matronly, and is traditionally associated with hospitals and things like that. It is easily recognized by the curled scrolls which appear at the top of the column.

The Corinthian is more refined again, and has the most elegant proportions of the orders. It is said to have the character of a graceful young maiden, and was particularly favored by the Romans when they built their temples and other public buildings.

And the Composite is sort of a combination of the Ionic and the Corinthian, and is the grandest of all of them.

So you have a sort of sliding scale according to the expenses, location, character and so on, and any particular building will probably lend itself naturally to one of the five.

Each of the orders is actually made up of small little building blocks, similar to words or musical notes, which are different shaped moldings. When you put many of them together, you get groupings which take on a specific character. So the DNA of classical architecture are molding shapes and profiles, and the basics of learning classical architecture are about understanding how you put all of these principles together.

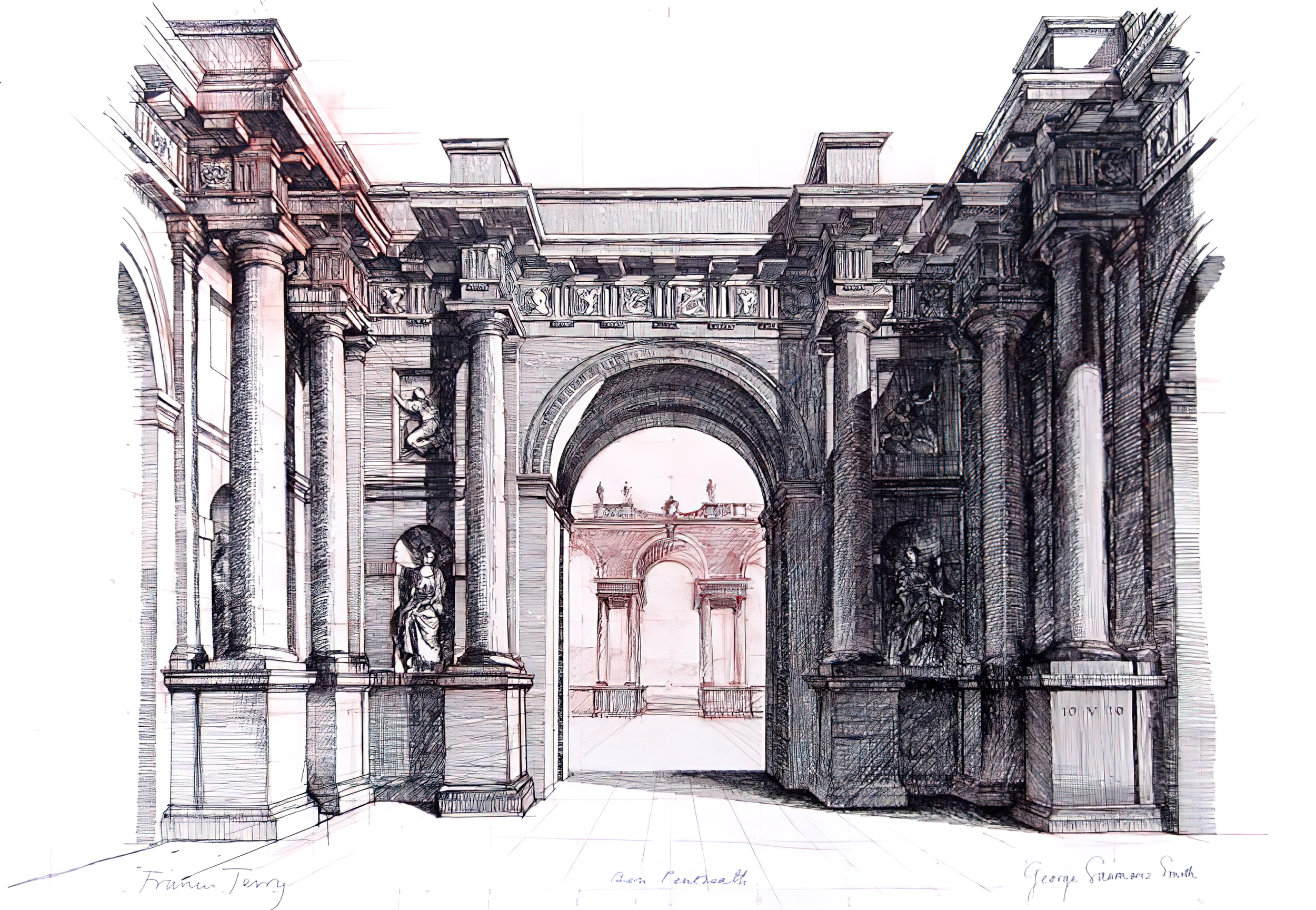

ARCHITECTURAL DRAWING BY BEN PENTREATH, GEORGE SAUMAREZ SMITH AND FRANCIS TERRY

It’s fascinating that the Orders are an aesthetic, as well as a functional and cultural guide in the design process.

Yes, everything is all mixed up together. For example, depending on what climate or scale you are working in, different combinations are good at shedding water, or at casting shadows in a particular way. And some combinations of moldings, like a convex molding followed by a concave one with a little square in between them, are very well rehearsed forms that we instinctively recognize when we look at buildings.

But people don’t always stop to look, and break them down into their individual components. They just look at a classical building and say ‘oh that's beautiful’, but don’t actually pull it apart. I suppose it's very similar to the other arts, like in poetry or music. As a casual listener or observer, you don’t need to know how something works, you just let it wash over you. But if you want to practice it, you have to understand the technique behind it.

In your TEDx talk you mention the current trend of building tall glass buildings that often look the same in cities all over the world. How can classical buildings be utilized to create a sense of place that is relevant to the cultural environments in which they reside?

Although classical architecture comes from western antiquity, it has been used all over the world by different cultures in different times, with different materials. So even though in a way it's a very formal kind of language, when this language is applied in a specific cultural environment, over time and through use it becomes a kind of vernacular. And so you get a sense of a very strong local culture, while still seeing through the framing of a more worldwide tradition.

You also mention how classical architecture can be more environmentally sustainable. Can you say more about this?

Yes, well in some ways it goes back to the vernacular, because classical buildings have always been built in different places using local materials. Particularly when materials were scarce, they just used whatever was at hand. And I think that’s really important wherever we are working- trying to draw from the materials that are directly available to us.

But it's also about designing something that's going to last a long time. And although a lot of that is about construction, it's about aesthetics as well. No building is maintenance free, and we know that for buildings to really last a long time, lots of people have to love them and look after them.

Yet what's happened to a lot of buildings built in the 1950’s, 60’s and even 70’s, is that they haven’t been loved and are now beyond repair. So I wouldn’t say that classical buildings never need to be maintained, but if properly built they should be very robust, and because they are beautiful, they will be cared for and looked after.

NEW BUILDINGS DESIGNED BY GEORGE AT POUNDBURY, DORSET

Also I feel that because the whole issue of sustainability has become so widespread, now no matter what kind of architecture you do, everyone says that it's sustainable. So I’m a little bit skeptical when people say that they build highly sustainable buildings, and then often when you see them they look a bit like a spaceship. My view is that the best way of designing sustainably is to create buildings that are well built and robust and don’t require lots of maintenance, which people are going to love and look after.

TIMELESS LANGUAGE

What are some simple ways someone who resonates with classical architecture can learn its language, and begin to appreciate it more?

I think the best thing to do is to go out and draw, and use one’s eyes. Very often people ask ‘how can I be taught to do this?’ and I think because I’ve never really had teachers who could give me the answers, I learned that instead of asking questions you can go out and look around a lot and draw, and start to figure it out for yourself. And if one has the time, that is probably the best way of learning.

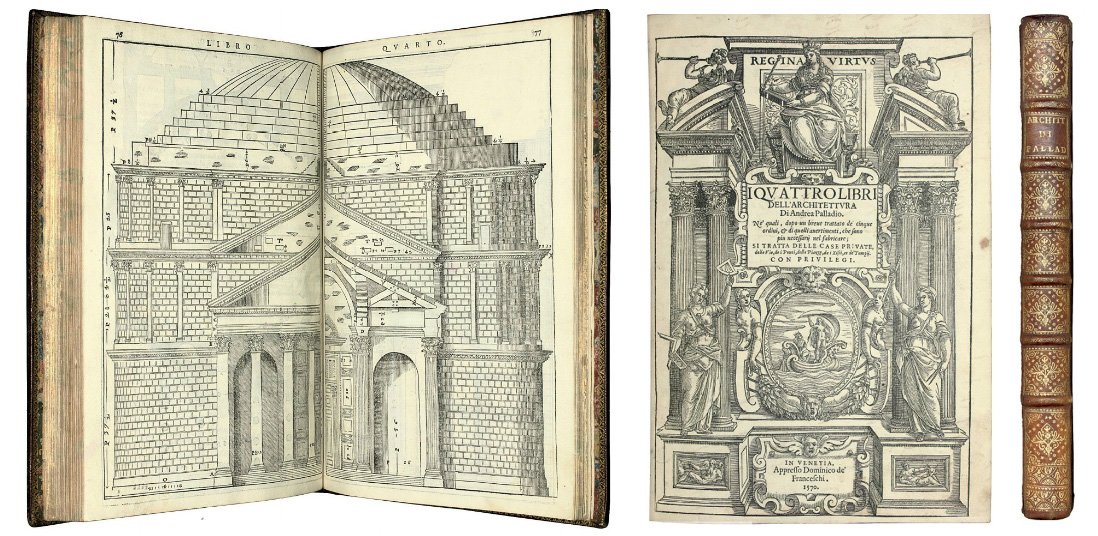

Of course there are also lots of books from over the last 500 years on how to do classical architecture well, some of them which are rather charmingly outdated. And yet it's a remarkable thing that it's still possible to pick up a book that was published 500 years ago, read through its pages, and do something directly from those pages.

ANDREA PALLADIO, THE FOUR BOOKS OF ARCHITECTURE, 1570

For example, you can pick up what Palladio wrote in the 16th century and use all of the same moldings on a brand new building today. Where if it was say a medical treatise, you wouldn’t dream of operating on somebody in the same way that they did 500 years ago. But there is something very valuable about the timelessness of classical architecture, and something very relevant even about the old books.

You often hear the famous Goethe quote ‘Architecture is frozen music’, and that many classical buildings have been built based on fundamental proportions that parallel musical ratios. In your experience of measuring buildings, have you found this to be true?

Well, in the 20th century there was this whole idea that the beauty of classical architecture was either related to number (geometry) or to harmonics. So there were long books written about harmonic proportion, geometric proportion and so on, and this idea had prevalence among a lot of architects- the theory that there’s a sort of secret to classical architecture that’s not about moldings or construction or anything like that, but rather it’s all about ratios and proportions.

Personally I’ve found by measuring old buildings that those who built them tended to work in very pragmatic ways, often using whole numbers in feet or inches, or whatever units of measure they were working in. I feel that when you're on the building site, pragmatic ways of doing things are always preferable to complicated things like the golden section and the fibonacci series, or whatever it may be. I feel that architecture is essentially a visual art, and although I very much appreciate mathematics and music and all of those things, I think it can be a mistake if we try to link them too closely.

BUILDING LOCALLY AND ABROAD

What are some of your favorite projects that you have worked on, past or present?

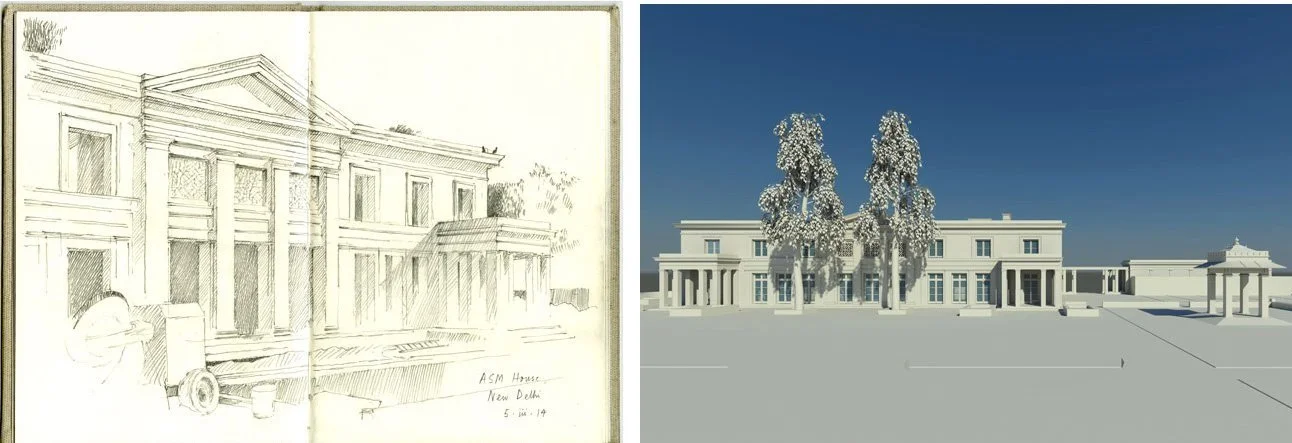

I'm building a house at the moment in New Dehli, India. It feels quite glamorous to be doing something so far away, yet because I’m a great believer in local traditions and local materials, I wouldn’t normally be working at this kind of distance. However, because even today New Dehli still has a strong British feel to it, it actually seems rather natural to be building a home there which is quite British in character.

SKETCH AND MODEL OF NEW DEHLI HOME

And we’ve actually been able to build much more traditionally than we could ever do here in the UK, partly because labor is much cheaper in India, and partly because we were able to build solid walls, whereas here everything is generally either frame construction or cavity wall. So we are building very solidly, and that feels like a good thing to me.

And the middle of New Dehli is full of interesting architecture, some of it built by the British, and some of it much older- Mughal temples and things, and then some a bit more recent. So it's a great privilege to be working somewhere so precious and diverse.

NEW BOND STREET ART GALLERY

Another project I loved doing was an art gallery in the middle of London on New Bond Street, an area that has lots of art dealers and jewelers and fashion houses and so on. We built a brand new building there for a fine art dealer, and because of the prominence of the street and their business, the quality had to be very good. It's completely stone built, has a sculptured facade, and was just a lovely project. And as the clients were art dealers, they appreciated the aesthetics and the commissioning process, which was really great as well.

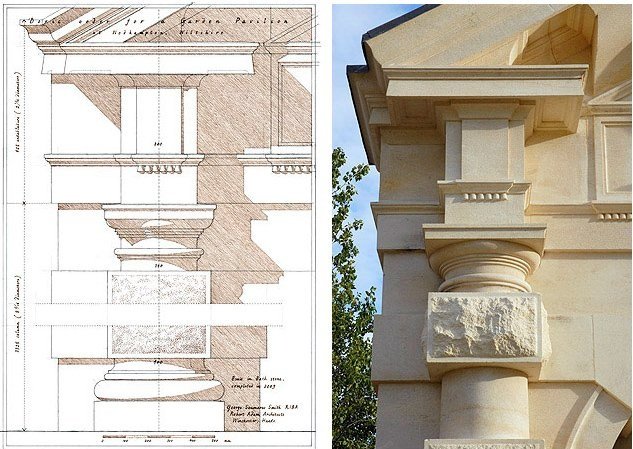

DETAIL OF SCULPTURED FACADE

However most of my work is building houses for people. I would love to do more public work, but the reality is that the commissioning of public buildings is very politically driven. The process of building houses is much simpler, because you are normally only working with a family, and all they want is a beautiful building. So in many ways it's much more straightforward.

DISPELLING MYTHS, DISCOVERING POTENTIAL

What kinds of political challenges have you run into within the public sector? Do they pertain to the cost of materials? Or a lack of knowledge in construction? Or perhaps a clash of paradigms?

It's fascinating that when you start talking about classical architecture, people always come out with reasons why you can’t do it, almost as a defense mechanism. They’ve got a whole list of reasons, and none of these reasons really have any weight to them.

For example, we have found that you can build a really good traditional building using top quality materials for the same cost as an equivalent building in any other style.

Another very typical one is when people say you can’t do this anymore because you can’t get the craftsmen, which is also untrue. If you were a stonemason and you went through an apprenticeship, you would learn all of the skills you need to build classical buildings. In fact, when we draw something up and invite workers to price for it, they’re usually more than willing to do it, because if you are a craftsman, you appreciate something with a challenge.

DETAIL OF A NEW PALLADIAN VILLA

Then they say we can’t do it because the construction isn’t the same. That’s inaccurate because every period has built classical buildings differently- they were built in brick and concrete clad with marble by the romans, the greeks were building in solid stone, and they were built using steel frames in the 1920‘s. So people always give reasons why you can’t do it... I feel it would be nice if people would start coming up with reasons why you can do it, rather than why you can’t (laughs).

And one last one, which is very unfortunate, and maybe why not enough public buildings are commissioned here, is because in recent memory people think that classicism is associated with a certain kind of political regime. This of course is simply not true, as for example in America in the 18th century it was very much associated with democracy, because they saw the links with the Greek world. And so because classical architecture has represented so many things throughout history, I think it’s wrong to reduce it to any one of them in particular.

MANOR HOUSE ALTERATIONS AND RESTORATION, HAMPSHIRE

I think for anyone who appreciates classical beauty and aesthetics, it's actually very encouraging to hear that it is much more about our frame of mind that is keeping us from doing it, rather than the challenges of cost and resources.

And we need more people to do it as well. The more people who do it, the better everybody will get. Right now if you want to build a really beautiful classical house, there aren’t many people who can do it; whereas 300 years ago, you could just run out to your local builder. So there’s a big learning process to go through. But the first step is recognizing that there's something that needs to be learned. And many schools of architecture are just beginning to realize that.

It's very exciting to think that there is the potential for us to still create beautiful buildings, and that we may be on the verge of yet another new 'revival' of classical architecture.

Yes and I feel we are doing it with other things within our culture. The revolution that has happened in food in the last 20 years, I think that may need to happen in the arts. The reconnection with things that are properly organic and local and based in tradition. It could happen. And now you walk around and see folk music for instance that has completely gone from a very minority interest into the mainstream in recent years. So with architecture, I truly think it can happen.